Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal

Dennis Donovan's Journal

March 30, 2019

No No Song, performed by Ringo, but written by Hoyt (and accompanied by the Smothers!)

March 30, 2019

I remember the initial confusion about whether Reagan was actually hit by gunfire. ABC's Frank Reynolds' frustration is evident as he finds out Reagan was hit:

38 Years Ago Today; Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attempted_assassination_of_Ronald_Reagan

On March 30, 1981, President Ronald Reagan and three others were shot and wounded by John Hinckley Jr. in Washington, D.C., as they were leaving a speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel. Hinckley's motivation for the attack was to impress actress Jodie Foster, who had played the role of a child prostitute in the 1976 film Taxi Driver. After seeing the film, Hinckley had developed an obsession with Foster.

Reagan was struck by a single bullet that broke a rib, punctured a lung, and caused serious internal bleeding, but he recovered quickly. No formal invocation of presidential succession took place, although Secretary of State Alexander Haig stated that he was "in control here" while Vice President George H. W. Bush returned to Washington.

Besides Reagan, White House Press Secretary James Brady, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy, and police officer Thomas Delahanty were also wounded. All three survived, but Brady suffered brain damage and was permanently disabled; Brady's death in 2014 was considered homicide because it was ultimately caused by this injury.

A federal judge subpoenaed Foster to testify at Hinckley's trial, and he was found not guilty by reason of insanity on charges of attempting to assassinate the president. Hinckley remained confined to a psychiatric facility. In January 2015, federal prosecutors announced that they would not charge Hinckley with Brady's death, despite the medical examiner's classification of his death as a homicide. On July 27, 2016, it was announced he would be released by August 5 to live with his mother in Williamsburg, Virginia; he was subsequently released on September 10.

<snip>

Assassination attempt

On March 21, 1981, new president Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy visited Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. for a fundraising event. Reagan recalled,

Speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel

On March 28, Hinckley arrived in Washington, D.C. by bus and checked into the Park Central Hotel. He noticed Reagan's schedule that was published in The Washington Star and decided it was time to act. Hinckley knew that he might be killed during the assassination attempt, and he wrote but did not mail a letter to Foster about two hours prior to his attempt on the president's life. In the letter, he said that he hoped to impress her with the magnitude of his action and that he would "abandon the idea of getting Reagan in a second if I could only win your heart and live out the rest of my life with you."

On March 30, Reagan delivered a luncheon address to AFL–CIO representatives at the Washington Hilton Hotel. The hotel was considered the safest venue in Washington because of its secure, enclosed passageway called "President's Walk", which was built after the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. Reagan entered the building through the passageway around 1:45 p.m., waving to a crowd of news media and citizens. The Secret Service had required him to wear a bulletproof vest for some events, but Reagan was not wearing one for the speech, because his only public exposure would be the 30 feet (9 m) between the hotel and his limousine, and the agency did not require vests for its agents that day. No one saw Hinckley behaving in an unusual way; witnesses who reported him as "fidgety" and "agitated" apparently confused Hinckley with another person that the Secret Service had been monitoring.

Shooting

At 2:27 p.m., Reagan exited the hotel through "President's Walk" and its T Street NW exit toward his waiting limousine as Hinckley waited within the crowd of admirers. The Secret Service had extensively screened those attending the president's speech. In a "colossal mistake", the agency allowed an unscreened group to stand within 15 ft (4.6 m) of him, behind a rope line. As several hundred people applauded Reagan, reporters standing behind a rope barricade 20 feet away asked questions. As Mike Putzel of the Associated Press shouted "Mr. President—", Reagan unexpectedly passed right in front of Hinckley. Believing he would never get a better chance, Hinckley fired a Röhm RG-14 .22 LR blue steel revolver six times in 1.7 seconds, missing the president with all six shots.

The first bullet hit White House Press Secretary James Brady in the head and the second hit District of Columbia police officer Thomas Delahanty in the back of his neck as he turned to protect Reagan. Hinckley now had a clear shot at the president, but the third bullet overshot him and hit the window of a building across the street. As Special Agent in Charge Jerry Parr quickly pushed Reagan into the limousine, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy put himself in the line of fire and spread his body in front of Reagan to make himself a target. McCarthy stepped in front of President Reagan, saving the president from harm at considerable risk to his own life. He was struck in the abdomen by the fourth bullet. The fifth bullet hit the bullet-resistant glass of the window on the open side door of the limousine. The sixth and final bullet ricocheted off the armored side of the limousine and hit the president in the left underarm, grazing a rib and lodging in his lung, causing it to partially collapse, and stopping less than an inch (25 mm) from his heart. Parr's prompt reaction had saved Reagan from being hit in the head.

After the shooting, Alfred Antenucci, a Cleveland, Ohio, labor official who stood nearby Hinckley, was the first to respond. He saw the gun and hit Hinckley in the head, pulling the shooter down to the ground. Within two seconds agent Dennis McCarthy (no relation to agent Timothy McCarthy) dove onto Hinckley as others threw him to the ground; intent on protecting Hinckley, and to avoid what happened to Lee Harvey Oswald, McCarthy had to "strike two citizens" to force them to release him. Agent Robert Wanko (misidentified as "Steve Wanko" in a newspaper report) took an Uzi submachine gun from a briefcase to cover the president's evacuation and to deter a potential group attack.

The day after the shooting, Hinckley's gun was given to the ATF, which traced its origin. In just 16 minutes, agents found that the gun had been purchased at Rocky's Pawn Shop in Dallas, Texas. It had been loaded with six "Devastator" brand cartridges, which contained small aluminum and lead azide explosive charges designed to explode on contact; the bullet that hit Brady was the only one that exploded. On April 2, after learning that the others could explode at any time, volunteer doctors wearing bulletproof vests removed the bullet from Delahanty's neck.

George Washington University Hospital

After the Secret Service first announced "shots fired" over its radio network at 2:27 p.m. Reagan—codename "Rawhide"—was taken away by the agents in the limousine ("Stagecoach" ). At first, no one knew that he had been shot, and Parr stated that "Rawhide is OK...we're going to Crown" (the White House), as he preferred its medical facilities to an unsecured hospital.

Reagan was in great pain from the bullet that struck his rib, and he believed that the rib had cracked when Parr pushed him into the limousine. When the agent checked him for gunshot wounds, however, Reagan coughed up bright, frothy blood. Although the president believed that he had cut his lip, Parr believed that the cracked rib had punctured Reagan's lung and ordered the motorcade to divert to nearby George Washington University Hospital, which the Secret Service periodically inspected for use. The limousine arrived there less than four minutes after leaving the hotel, while other agents took Hinckley to a DC jail, and Nancy Reagan ("Rainbow" ) left the White House for the hospital.

Although Parr had requested a stretcher, none were ready at the hospital, and it did not normally keep a stretcher at the emergency department's entrance. Reagan exited the limousine and insisted on walking. Reagan acted casual and smiled at onlookers as he walked in. While he entered the hospital unassisted, once inside the president complained of difficulty breathing, his knees buckled, and he went down on one knee; Parr and others assisted him into the emergency department. The Physician to the President, Daniel Ruge, arrived with Reagan; believing that the president might have had a heart attack, he insisted that the hospital's trauma team, and not himself or specialists from elsewhere, operate on him as they would any other patient. When a hospital employee asked Reagan aide Michael Deaver for the patient's name and address, only when Deaver stated "1600 Pennsylvania" did the worker realize that the president of the United States was in the emergency department.

The team, led by Joseph Giordano, cut off Reagan's "thousand dollar" custom-made suit to examine him, much to Reagan's anger. Military officers, including the one who carried the nuclear football, unsuccessfully tried to prevent FBI agents from confiscating the suit, Reagan's wallet, and other possessions as evidence; the Gold Codes card was in the wallet, and the FBI did not return it until two days later. The medical personnel found that Reagan's systolic blood pressure was 60 versus the normal 140, indicating that he was in shock, and knew that most 70-year-olds in the president's condition would not survive. Reagan was in excellent physical health, however, and also was shot by the .22 caliber instead of the larger .38 as was first feared. They treated him with intravenous fluids, oxygen, tetanus toxoid, and chest tubes, and surprised Parr—who still believed that he had cracked the president's rib—by finding the entrance of the gunshot wound. Brady and the wounded agent McCarthy were operated on near the president; when his wife arrived in the emergency department, Reagan remarked to her, "Honey, I forgot to duck", borrowing boxer Jack Dempsey's line to his wife the night he was beaten by Gene Tunney. While intubated, he scribbled to a nurse, "All in all, I'd rather be in Philadelphia", borrowing a line from W. C. Fields. Although Reagan came close to death, the team's quick action—and Parr's decision to drive to the hospital instead of the White House—likely saved the president's life, and within 30 minutes Reagan left the emergency department for surgery with normal blood pressure.

The chief of thoracic surgery, Benjamin L. Aaron, decided to perform a thoracotomy lasting 105 minutes because the bleeding persisted. Ultimately, Reagan lost over half of his blood volume in the emergency department and during surgery, which removed the bullet. In the operating room, Reagan removed his oxygen mask to joke, "I hope you are all Republicans." The doctors and nurses laughed, and Giordano, a liberal Democrat, replied, "Today, Mr. President, we are all Republicans." Reagan's post-operative course was complicated by fever, which was treated with multiple antibiotics. The surgery was routine enough that they predicted Reagan would be able to leave the hospital in two weeks and return to work at the Oval Office within a month.

</snip>

On March 30, 1981, President Ronald Reagan and three others were shot and wounded by John Hinckley Jr. in Washington, D.C., as they were leaving a speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel. Hinckley's motivation for the attack was to impress actress Jodie Foster, who had played the role of a child prostitute in the 1976 film Taxi Driver. After seeing the film, Hinckley had developed an obsession with Foster.

Reagan was struck by a single bullet that broke a rib, punctured a lung, and caused serious internal bleeding, but he recovered quickly. No formal invocation of presidential succession took place, although Secretary of State Alexander Haig stated that he was "in control here" while Vice President George H. W. Bush returned to Washington.

Besides Reagan, White House Press Secretary James Brady, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy, and police officer Thomas Delahanty were also wounded. All three survived, but Brady suffered brain damage and was permanently disabled; Brady's death in 2014 was considered homicide because it was ultimately caused by this injury.

A federal judge subpoenaed Foster to testify at Hinckley's trial, and he was found not guilty by reason of insanity on charges of attempting to assassinate the president. Hinckley remained confined to a psychiatric facility. In January 2015, federal prosecutors announced that they would not charge Hinckley with Brady's death, despite the medical examiner's classification of his death as a homicide. On July 27, 2016, it was announced he would be released by August 5 to live with his mother in Williamsburg, Virginia; he was subsequently released on September 10.

<snip>

Assassination attempt

On March 21, 1981, new president Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy visited Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. for a fundraising event. Reagan recalled,

I looked up at the presidential box above the stage where Abe Lincoln had been sitting the night he was shot and felt a curious sensation ... I thought that even with all the Secret Service protection we now had, it was probably still possible for someone who had enough determination to get close enough to the president to shoot him.

Speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel

On March 28, Hinckley arrived in Washington, D.C. by bus and checked into the Park Central Hotel. He noticed Reagan's schedule that was published in The Washington Star and decided it was time to act. Hinckley knew that he might be killed during the assassination attempt, and he wrote but did not mail a letter to Foster about two hours prior to his attempt on the president's life. In the letter, he said that he hoped to impress her with the magnitude of his action and that he would "abandon the idea of getting Reagan in a second if I could only win your heart and live out the rest of my life with you."

On March 30, Reagan delivered a luncheon address to AFL–CIO representatives at the Washington Hilton Hotel. The hotel was considered the safest venue in Washington because of its secure, enclosed passageway called "President's Walk", which was built after the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. Reagan entered the building through the passageway around 1:45 p.m., waving to a crowd of news media and citizens. The Secret Service had required him to wear a bulletproof vest for some events, but Reagan was not wearing one for the speech, because his only public exposure would be the 30 feet (9 m) between the hotel and his limousine, and the agency did not require vests for its agents that day. No one saw Hinckley behaving in an unusual way; witnesses who reported him as "fidgety" and "agitated" apparently confused Hinckley with another person that the Secret Service had been monitoring.

Shooting

At 2:27 p.m., Reagan exited the hotel through "President's Walk" and its T Street NW exit toward his waiting limousine as Hinckley waited within the crowd of admirers. The Secret Service had extensively screened those attending the president's speech. In a "colossal mistake", the agency allowed an unscreened group to stand within 15 ft (4.6 m) of him, behind a rope line. As several hundred people applauded Reagan, reporters standing behind a rope barricade 20 feet away asked questions. As Mike Putzel of the Associated Press shouted "Mr. President—", Reagan unexpectedly passed right in front of Hinckley. Believing he would never get a better chance, Hinckley fired a Röhm RG-14 .22 LR blue steel revolver six times in 1.7 seconds, missing the president with all six shots.

The first bullet hit White House Press Secretary James Brady in the head and the second hit District of Columbia police officer Thomas Delahanty in the back of his neck as he turned to protect Reagan. Hinckley now had a clear shot at the president, but the third bullet overshot him and hit the window of a building across the street. As Special Agent in Charge Jerry Parr quickly pushed Reagan into the limousine, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy put himself in the line of fire and spread his body in front of Reagan to make himself a target. McCarthy stepped in front of President Reagan, saving the president from harm at considerable risk to his own life. He was struck in the abdomen by the fourth bullet. The fifth bullet hit the bullet-resistant glass of the window on the open side door of the limousine. The sixth and final bullet ricocheted off the armored side of the limousine and hit the president in the left underarm, grazing a rib and lodging in his lung, causing it to partially collapse, and stopping less than an inch (25 mm) from his heart. Parr's prompt reaction had saved Reagan from being hit in the head.

After the shooting, Alfred Antenucci, a Cleveland, Ohio, labor official who stood nearby Hinckley, was the first to respond. He saw the gun and hit Hinckley in the head, pulling the shooter down to the ground. Within two seconds agent Dennis McCarthy (no relation to agent Timothy McCarthy) dove onto Hinckley as others threw him to the ground; intent on protecting Hinckley, and to avoid what happened to Lee Harvey Oswald, McCarthy had to "strike two citizens" to force them to release him. Agent Robert Wanko (misidentified as "Steve Wanko" in a newspaper report) took an Uzi submachine gun from a briefcase to cover the president's evacuation and to deter a potential group attack.

The day after the shooting, Hinckley's gun was given to the ATF, which traced its origin. In just 16 minutes, agents found that the gun had been purchased at Rocky's Pawn Shop in Dallas, Texas. It had been loaded with six "Devastator" brand cartridges, which contained small aluminum and lead azide explosive charges designed to explode on contact; the bullet that hit Brady was the only one that exploded. On April 2, after learning that the others could explode at any time, volunteer doctors wearing bulletproof vests removed the bullet from Delahanty's neck.

George Washington University Hospital

After the Secret Service first announced "shots fired" over its radio network at 2:27 p.m. Reagan—codename "Rawhide"—was taken away by the agents in the limousine ("Stagecoach" ). At first, no one knew that he had been shot, and Parr stated that "Rawhide is OK...we're going to Crown" (the White House), as he preferred its medical facilities to an unsecured hospital.

Reagan was in great pain from the bullet that struck his rib, and he believed that the rib had cracked when Parr pushed him into the limousine. When the agent checked him for gunshot wounds, however, Reagan coughed up bright, frothy blood. Although the president believed that he had cut his lip, Parr believed that the cracked rib had punctured Reagan's lung and ordered the motorcade to divert to nearby George Washington University Hospital, which the Secret Service periodically inspected for use. The limousine arrived there less than four minutes after leaving the hotel, while other agents took Hinckley to a DC jail, and Nancy Reagan ("Rainbow" ) left the White House for the hospital.

Although Parr had requested a stretcher, none were ready at the hospital, and it did not normally keep a stretcher at the emergency department's entrance. Reagan exited the limousine and insisted on walking. Reagan acted casual and smiled at onlookers as he walked in. While he entered the hospital unassisted, once inside the president complained of difficulty breathing, his knees buckled, and he went down on one knee; Parr and others assisted him into the emergency department. The Physician to the President, Daniel Ruge, arrived with Reagan; believing that the president might have had a heart attack, he insisted that the hospital's trauma team, and not himself or specialists from elsewhere, operate on him as they would any other patient. When a hospital employee asked Reagan aide Michael Deaver for the patient's name and address, only when Deaver stated "1600 Pennsylvania" did the worker realize that the president of the United States was in the emergency department.

The team, led by Joseph Giordano, cut off Reagan's "thousand dollar" custom-made suit to examine him, much to Reagan's anger. Military officers, including the one who carried the nuclear football, unsuccessfully tried to prevent FBI agents from confiscating the suit, Reagan's wallet, and other possessions as evidence; the Gold Codes card was in the wallet, and the FBI did not return it until two days later. The medical personnel found that Reagan's systolic blood pressure was 60 versus the normal 140, indicating that he was in shock, and knew that most 70-year-olds in the president's condition would not survive. Reagan was in excellent physical health, however, and also was shot by the .22 caliber instead of the larger .38 as was first feared. They treated him with intravenous fluids, oxygen, tetanus toxoid, and chest tubes, and surprised Parr—who still believed that he had cracked the president's rib—by finding the entrance of the gunshot wound. Brady and the wounded agent McCarthy were operated on near the president; when his wife arrived in the emergency department, Reagan remarked to her, "Honey, I forgot to duck", borrowing boxer Jack Dempsey's line to his wife the night he was beaten by Gene Tunney. While intubated, he scribbled to a nurse, "All in all, I'd rather be in Philadelphia", borrowing a line from W. C. Fields. Although Reagan came close to death, the team's quick action—and Parr's decision to drive to the hospital instead of the White House—likely saved the president's life, and within 30 minutes Reagan left the emergency department for surgery with normal blood pressure.

The chief of thoracic surgery, Benjamin L. Aaron, decided to perform a thoracotomy lasting 105 minutes because the bleeding persisted. Ultimately, Reagan lost over half of his blood volume in the emergency department and during surgery, which removed the bullet. In the operating room, Reagan removed his oxygen mask to joke, "I hope you are all Republicans." The doctors and nurses laughed, and Giordano, a liberal Democrat, replied, "Today, Mr. President, we are all Republicans." Reagan's post-operative course was complicated by fever, which was treated with multiple antibiotics. The surgery was routine enough that they predicted Reagan would be able to leave the hospital in two weeks and return to work at the Oval Office within a month.

</snip>

I remember the initial confusion about whether Reagan was actually hit by gunfire. ABC's Frank Reynolds' frustration is evident as he finds out Reagan was hit:

March 28, 2019

Never forget...

40 Years Ago Today; Three Mile Island Nuclear Accident

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Mile_Island_accident

The Three Mile Island accident was the partial meltdown of reactor number 2 of Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station (TMI-2) in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, near Harrisburg and subsequent radiation leak that occurred on March 28, 1979. It was the most significant accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history. The incident was rated a five on the seven-point International Nuclear Event Scale: Accident with wider consequences.

The accident began with failures in the non-nuclear secondary system, followed by a stuck-open pilot-operated relief valve in the primary system, which allowed large amounts of nuclear reactor coolant to escape. The mechanical failures were compounded by the initial failure of plant operators to recognize the situation as a loss-of-coolant accident due to inadequate training and human factors, such as human-computer interaction design oversights relating to ambiguous control room indicators in the power plant's user interface. In particular, a hidden indicator light led to an operator manually overriding the automatic emergency cooling system of the reactor because the operator mistakenly believed that there was too much coolant water present in the reactor and causing the steam pressure release.

The accident crystallized anti-nuclear safety concerns among activists and the general public, and resulted in new regulations for the nuclear industry. It has been cited to have been a catalyst to the decline of a new reactor construction program, a slowdown that was already underway in the 1970s. The partial meltdown resulted in the release of radioactive gases and radioactive iodine into the environment.

Anti-nuclear movement activists expressed worries about regional health effects from the accident. However, epidemiological studies analyzing the rate of cancer in and around the area since the accident, determined there was a small statistically non-significant increase in the rate and thus no causal connection linking the accident with these cancers has been substantiated. Cleanup started in August 1979, and officially ended in December 1993, with a total cleanup cost of about $1 billion.

President Jimmy Carter touring the TMI-2 control room on April 1, 1979, with NRR Director Harold Denton, Governor of Pennsylvania Dick Thornburgh and James Floyd, supervisor of TMI-2 operations

<snip>

Current status

Unit 1 had its license temporarily suspended following the incident at Unit 2. Although the citizens of the three counties surrounding the site voted by an overwhelming margin to retire Unit 1 permanently in a non-binding resolution in 1982, it was permitted to resume operations in 1985 following a 4-1 vote by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. General Public Utilities Corporation, the plant's owner, formed General Public Utilities Nuclear Corporation (GPUN) as a new subsidiary to own and operate the company's nuclear facilities, including Three Mile Island. The plant had previously been operated by Metropolitan Edison Company (Met-Ed), one of GPU's regional utility operating companies. In 1996, General Public Utilities shortened its name to GPU Inc. Three Mile Island Unit 1 was sold to AmerGen Energy Corporation, a joint venture between Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO), and British Energy, in 1998. In 2000, PECO merged with Unicom Corporation to form Exelon Corporation, which acquired British Energy's share of AmerGen in 2003. Today, AmerGen LLC is a fully owned subsidiary of Exelon Generation and owns TMI Unit 1, Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, and Clinton Power Station. These three units, in addition to Exelon's other nuclear units, are operated by Exelon Nuclear Inc., an Exelon subsidiary.

General Public Utilities was legally obliged to continue to maintain and monitor the site, and therefore retained ownership of Unit 2 when Unit 1 was sold to AmerGen in 1998. GPU Inc. was acquired by FirstEnergy Corporation in 2001, and subsequently dissolved. FirstEnergy then contracted out the maintenance and administration of Unit 2 to AmerGen. Unit 2 has been administered by Exelon Nuclear since 2003, when Exelon Nuclear's parent company, Exelon, bought out the remaining shares of AmerGen, inheriting FirstEnergy's maintenance contract. Unit 2 continues to be licensed and regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in a condition known as Post Defueling Monitored Storage (PDMS).

The TMI-2 reactor has been permanently shut down with the reactor coolant system drained, the radioactive water decontaminated and evaporated, radioactive waste shipped off-site, reactor fuel and core debris shipped off-site to a Department of Energy facility, and the remainder of the site being monitored. The owner planned to keep the facility in long-term, monitoring storage until the operating license for the TMI-1 plant expired, at which time both plants would be decommissioned. In 2009, the NRC granted a license extension which allowed the TMI-1 reactor to operate until April 19, 2034. In 2017 it was announced that operations would cease by 2019 due to financial pressure from cheap natural gas.

</snip>

The Three Mile Island accident was the partial meltdown of reactor number 2 of Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station (TMI-2) in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, near Harrisburg and subsequent radiation leak that occurred on March 28, 1979. It was the most significant accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history. The incident was rated a five on the seven-point International Nuclear Event Scale: Accident with wider consequences.

The accident began with failures in the non-nuclear secondary system, followed by a stuck-open pilot-operated relief valve in the primary system, which allowed large amounts of nuclear reactor coolant to escape. The mechanical failures were compounded by the initial failure of plant operators to recognize the situation as a loss-of-coolant accident due to inadequate training and human factors, such as human-computer interaction design oversights relating to ambiguous control room indicators in the power plant's user interface. In particular, a hidden indicator light led to an operator manually overriding the automatic emergency cooling system of the reactor because the operator mistakenly believed that there was too much coolant water present in the reactor and causing the steam pressure release.

The accident crystallized anti-nuclear safety concerns among activists and the general public, and resulted in new regulations for the nuclear industry. It has been cited to have been a catalyst to the decline of a new reactor construction program, a slowdown that was already underway in the 1970s. The partial meltdown resulted in the release of radioactive gases and radioactive iodine into the environment.

Anti-nuclear movement activists expressed worries about regional health effects from the accident. However, epidemiological studies analyzing the rate of cancer in and around the area since the accident, determined there was a small statistically non-significant increase in the rate and thus no causal connection linking the accident with these cancers has been substantiated. Cleanup started in August 1979, and officially ended in December 1993, with a total cleanup cost of about $1 billion.

President Jimmy Carter touring the TMI-2 control room on April 1, 1979, with NRR Director Harold Denton, Governor of Pennsylvania Dick Thornburgh and James Floyd, supervisor of TMI-2 operations

<snip>

Current status

Unit 1 had its license temporarily suspended following the incident at Unit 2. Although the citizens of the three counties surrounding the site voted by an overwhelming margin to retire Unit 1 permanently in a non-binding resolution in 1982, it was permitted to resume operations in 1985 following a 4-1 vote by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. General Public Utilities Corporation, the plant's owner, formed General Public Utilities Nuclear Corporation (GPUN) as a new subsidiary to own and operate the company's nuclear facilities, including Three Mile Island. The plant had previously been operated by Metropolitan Edison Company (Met-Ed), one of GPU's regional utility operating companies. In 1996, General Public Utilities shortened its name to GPU Inc. Three Mile Island Unit 1 was sold to AmerGen Energy Corporation, a joint venture between Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO), and British Energy, in 1998. In 2000, PECO merged with Unicom Corporation to form Exelon Corporation, which acquired British Energy's share of AmerGen in 2003. Today, AmerGen LLC is a fully owned subsidiary of Exelon Generation and owns TMI Unit 1, Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, and Clinton Power Station. These three units, in addition to Exelon's other nuclear units, are operated by Exelon Nuclear Inc., an Exelon subsidiary.

General Public Utilities was legally obliged to continue to maintain and monitor the site, and therefore retained ownership of Unit 2 when Unit 1 was sold to AmerGen in 1998. GPU Inc. was acquired by FirstEnergy Corporation in 2001, and subsequently dissolved. FirstEnergy then contracted out the maintenance and administration of Unit 2 to AmerGen. Unit 2 has been administered by Exelon Nuclear since 2003, when Exelon Nuclear's parent company, Exelon, bought out the remaining shares of AmerGen, inheriting FirstEnergy's maintenance contract. Unit 2 continues to be licensed and regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in a condition known as Post Defueling Monitored Storage (PDMS).

The TMI-2 reactor has been permanently shut down with the reactor coolant system drained, the radioactive water decontaminated and evaporated, radioactive waste shipped off-site, reactor fuel and core debris shipped off-site to a Department of Energy facility, and the remainder of the site being monitored. The owner planned to keep the facility in long-term, monitoring storage until the operating license for the TMI-1 plant expired, at which time both plants would be decommissioned. In 2009, the NRC granted a license extension which allowed the TMI-1 reactor to operate until April 19, 2034. In 2017 it was announced that operations would cease by 2019 due to financial pressure from cheap natural gas.

</snip>

Never forget...

March 27, 2019

9.2!!!

On edit: The same (as the pic at the top) view today:

55 Years Ago Today; Good Friday Earthquake - Anchorage, AK

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1964_Alaska_earthquake

Fourth Avenue in Anchorage, Alaska, looking east from near Barrow Street. The southern edge of one of several landslides in Anchorage, this one covered an area of over a dozen blocks, including five blocks along the north side of Fourth Avenue. Most of the area was razed and made an urban renewal district

The 1964 Alaskan earthquake, also known as the Great Alaskan earthquake and Good Friday earthquake, occurred at 5:36 PM AKST on Good Friday, March 27. Across south-central Alaska, ground fissures, collapsing structures, and tsunamis resulting from the earthquake caused about 131 deaths.

Lasting four minutes and thirty-eight seconds, the magnitude 9.2 megathrust earthquake remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in North American history, and the second most powerful earthquake recorded in world history. Six hundred miles (970 km) of fault ruptured at once and moved up to 60 ft (18 m), releasing about 500 years of stress buildup. Soil liquefaction, fissures, landslides, and other ground failures caused major structural damage in several communities and much damage to property. Anchorage sustained great destruction or damage to many inadequately earthquake-engineered houses, buildings, and infrastructure (paved streets, sidewalks, water and sewer mains, electrical systems, and other man-made equipment), particularly in the several landslide zones along Knik Arm. Two hundred miles (320 km) southwest, some areas near Kodiak were permanently raised by 30 feet (9 m). Southeast of Anchorage, areas around the head of Turnagain Arm near Girdwood and Portage dropped as much as 8 feet (2.4 m), requiring reconstruction and fill to raise the Seward Highway above the new high tide mark.

In Prince William Sound, Port Valdez suffered a massive underwater landslide, resulting in the deaths of 32 people between the collapse of the Valdez city harbor and docks, and inside the ship that was docked there at the time. Nearby, a 27-foot (8.2 m) tsunami destroyed the village of Chenega, killing 23 of the 68 people who lived there; survivors out-ran the wave, climbing to high ground. Post-quake tsunamis severely affected Whittier, Seward, Kodiak, and other Alaskan communities, as well as people and property in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. Tsunamis also caused damage in Hawaii and Japan. Evidence of motion directly related to the earthquake was also reported from Florida and Texas.

</snip>

Fourth Avenue in Anchorage, Alaska, looking east from near Barrow Street. The southern edge of one of several landslides in Anchorage, this one covered an area of over a dozen blocks, including five blocks along the north side of Fourth Avenue. Most of the area was razed and made an urban renewal district

The 1964 Alaskan earthquake, also known as the Great Alaskan earthquake and Good Friday earthquake, occurred at 5:36 PM AKST on Good Friday, March 27. Across south-central Alaska, ground fissures, collapsing structures, and tsunamis resulting from the earthquake caused about 131 deaths.

Lasting four minutes and thirty-eight seconds, the magnitude 9.2 megathrust earthquake remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in North American history, and the second most powerful earthquake recorded in world history. Six hundred miles (970 km) of fault ruptured at once and moved up to 60 ft (18 m), releasing about 500 years of stress buildup. Soil liquefaction, fissures, landslides, and other ground failures caused major structural damage in several communities and much damage to property. Anchorage sustained great destruction or damage to many inadequately earthquake-engineered houses, buildings, and infrastructure (paved streets, sidewalks, water and sewer mains, electrical systems, and other man-made equipment), particularly in the several landslide zones along Knik Arm. Two hundred miles (320 km) southwest, some areas near Kodiak were permanently raised by 30 feet (9 m). Southeast of Anchorage, areas around the head of Turnagain Arm near Girdwood and Portage dropped as much as 8 feet (2.4 m), requiring reconstruction and fill to raise the Seward Highway above the new high tide mark.

In Prince William Sound, Port Valdez suffered a massive underwater landslide, resulting in the deaths of 32 people between the collapse of the Valdez city harbor and docks, and inside the ship that was docked there at the time. Nearby, a 27-foot (8.2 m) tsunami destroyed the village of Chenega, killing 23 of the 68 people who lived there; survivors out-ran the wave, climbing to high ground. Post-quake tsunamis severely affected Whittier, Seward, Kodiak, and other Alaskan communities, as well as people and property in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. Tsunamis also caused damage in Hawaii and Japan. Evidence of motion directly related to the earthquake was also reported from Florida and Texas.

</snip>

9.2!!!

On edit: The same (as the pic at the top) view today:

March 27, 2019

42 Years Ago Today; The Tenerife Air Disaster

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tenerife_airport_disaster

On March 27, 1977, two Boeing 747 passenger jets, KLM Flight 4805 and Pan Am Flight 1736, collided on the runway at Los Rodeos Airport (now Tenerife North Airport), on the Spanish island of Tenerife, Canary Islands, killing 583 people, making it the deadliest accident in aviation history.

A terrorist incident at Gran Canaria Airport had caused many flights to be diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two aircraft involved in the accident. The airport quickly became congested with parked airplanes blocking the only taxiway and forcing departing aircraft to taxi on the runway instead. Patches of thick fog were drifting across the airfield, so that the aircraft and control tower were unable to see one another.

The collision occurred when the KLM airliner initiated its takeoff run while the Pan Am airliner, shrouded in fog, was still on the runway and about to turn off onto the taxiway. The impact and resulting fire killed everyone on board KLM 4805 and most of the occupants of Pan Am 1736, with only 61 survivors in the front section of the aircraft.

The subsequent investigation by Spanish authorities concluded that the primary cause of the accident was the KLM captain's decision to take off in the mistaken belief that a takeoff clearance from air traffic control (ATC) had been issued. Dutch investigators placed a greater emphasis on mutual misunderstanding in radio communications between the KLM crew and ATC, but ultimately KLM admitted that their crew was responsible for the accident and the airline agreed to financially compensate the relatives of all of the victims.

The disaster had a lasting influence on the industry, highlighting in particular the vital importance of using standardized phraseology in radio communications. Cockpit procedures were also reviewed, contributing to the establishment of crew resource management as a fundamental part of airline pilots' training.

<snip>

Disaster

Diversion of aircraft to Los Rodeos

Both flights had been routine until they approached the islands. At 13:15, a bomb planted by the separatist Canary Islands Independence Movement exploded in the terminal of Gran Canaria International Airport, injuring eight people. There had been a phone call warning of the bomb, and another call received soon afterwards made claims of a second bomb at the airport. The civil aviation authorities had therefore closed the airport temporarily after the explosion, and all incoming flights bound for Gran Canaria had been diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two Boeing 747 aircraft involved in the disaster. The Pan Am crew indicated that they would prefer to circle in a holding pattern until landing clearance was given, but they were ordered to divert to Tenerife.

Los Rodeos was a regional airport that could not easily accommodate all of the traffic diverted from Gran Canaria, which included five large airliners. The airport had only one runway and one major taxiway running parallel to it, with four short taxiways connecting the two. While waiting for Gran Canaria airport to reopen, the diverted airplanes took up so much space that they were having to park on the long taxiway, making it unavailable for the purpose of taxiing. Instead, departing aircraft needed to taxi along the runway to position themselves for takeoff, a procedure known as a backtaxi or backtrack.

The authorities reopened Gran Canaria airport once the bomb threat had been contained. The Pan Am plane was ready to depart from Tenerife, but access to the runway was being obstructed by the KLM plane and a refueling vehicle; the KLM captain had decided to fully refuel at Los Rodeos instead of Las Palmas, apparently to save time. The Pan Am aircraft was unable to maneuver around the refueling KLM, in order to reach the runway for takeoff, due to a lack of safe clearance between the two planes, which was just 3.7 meters (12 ft). The refueling took about 35 minutes, after which the passengers were brought back to the aircraft. The search for a missing Dutch family of four, who had not returned to the waiting KLM plane, delayed the flight even further. A tour guide had chosen not to reboard for the flight to Las Palmas, because she lived on Tenerife and thought it impractical to fly to Gran Canaria only to return to Tenerife the next day. She was therefore not on the KLM plane when the accident happened, and she would be the only survivor of those who flew from Amsterdam to Tenerife on Flight 4805.

Taxiing and takeoff preparations

The tower instructed the KLM to taxi down the entire length of the runway and then make a 180-degree turn to get into takeoff position. While the KLM was backtaxiing on the runway, the controller asked the flight crew to report when it was ready to copy the ATC clearance. Because the flight crew was performing the checklist, copying this clearance was postponed until the aircraft was in takeoff position on Runway 30.

Simplified map of runway, taxiways, and aircraft. The red star indicates the location of impact. Not to scale.

Shortly afterward, the Pan Am was instructed to follow the KLM down the same runway, exit it by taking the third exit on their left and then use the parallel taxiway. Initially, the crew was unclear as to whether the controller had told them to take the first or third exit. The crew asked for clarification and the controller responded emphatically by replying: "The third one, sir; one, two, three; third, third one." The crew began the taxi and proceeded to identify the unmarked taxiways using an airport diagram as they reached them.

The crew successfully identified the first two taxiways (C-1 and C-2), but their discussion in the cockpit never indicated that they had sighted the third taxiway (C-3), which they had been instructed to use. There were no markings or signs to identify the runway exits and they were in conditions of poor visibility. The Pan Am crew appeared to remain unsure of their position on the runway until the collision, which occurred near the intersection with the fourth taxiway (C-4).

The angle of the third taxiway would have required the plane to perform a 148-degree turn, which would lead back toward the still-crowded main apron. At the end of C-3, the Pan Am would have to make another 148-degree turn, in order to continue taxiing towards the start of the runway, similar to a mirrored letter "Z". Taxiway C-4 would have required two 35-degree-turns. A study carried out by the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) after the accident concluded that making the second 148-degree turn at the end of taxiway C-3 would have been "a practical impossibility." The official report from the Spanish authorities explains that the controller instructed the Pan Am aircraft to use the third taxiway because this was the earliest exit that they could take to reach the unobstructed section of the parallel taxiway.

Weather conditions at Los Rodeos

Los Rodeos airport is at 633 meters (2,077 ft) above sea level, which gives rise to cloud behavior that differs from that at many other airports. Clouds at 600 m (2,000 ft) above ground level at the nearby coast are at ground level at Los Rodeos. Drifting clouds of different densities cause wildly varying visibilities, from unhindered at one moment to below the minimums the next. The collision took place in a high-density cloud.

The Pan Am crew found themselves in poor and rapidly deteriorating visibility almost as soon as they entered the runway. According to the ALPA report, as the Pan Am aircraft taxied to the runway, the visibility was about 500 m (1,600 ft). Shortly after they turned onto the runway it decreased to less than 100 m (330 ft).

Meanwhile, the KLM plane was still in good visibility, but with clouds blowing down the runway towards them. The aircraft completed its 180-degree turn in relatively clear weather and lined up on Runway 30. The next cloud was 900 m (3,000 ft) down the runway and moving towards the aircraft at about 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h).

Communication misunderstandings

Immediately after lining up, the KLM captain advanced the throttles and the aircraft started to move forward. First officer Meurs advised him that ATC clearance had not yet been given, and captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten responded: "No, I know that. Go ahead, ask." Meurs then radioed the tower that they were "ready for takeoff" and "waiting for our ATC clearance". The KLM crew then received instructions that specified the route that the aircraft was to follow after takeoff. The instructions used the word "takeoff," but did not include an explicit statement that they were cleared for takeoff.

Meurs read the flight clearance back to the controller, completing the readback with the statement: "We are now at takeoff." Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten interrupted the co-pilot's read-back with the comment, "We're going."

The controller, who could not see the runway due to the fog, initially responded with "OK" (terminology that is nonstandard), which reinforced the KLM captain's misinterpretation that they had takeoff clearance. The controller's response of "OK" to the co-pilot's nonstandard statement that they were "now at takeoff" was likely due to his misinterpretation that they were in takeoff position and ready to begin the roll when takeoff clearance was received, but not in the process of taking off. The controller then immediately added "stand by for takeoff, I will call you", indicating that he had not intended the clearance to be interpreted as a takeoff clearance.

A simultaneous radio call from the Pan Am crew caused mutual interference on the radio frequency, which was audible in the KLM cockpit as a 3-second-long shrill sound, (or heterodyne). This caused the KLM crew to miss the crucial latter portion of the tower's response. The Pan Am crew's transmission was "We're still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736!" This message was also blocked by the interference and inaudible to the KLM crew. Either message, if heard in the KLM cockpit, would have alerted the crew to the situation and given them time to abort the takeoff attempt.

Due to the fog, neither crew was able to see the other plane on the runway ahead of them. In addition, neither of the aircraft could be seen from the control tower, and the airport was not equipped with ground radar.

After the KLM plane had started its takeoff roll, the tower instructed the Pan Am crew to "report when runway clear." The Pan Am crew replied: "OK, will report when we're clear." On hearing this, the KLM flight engineer expressed his concern about the Pan Am not being clear of the runway by asking the pilots in his own cockpit, "Is he not clear, that Pan American?" Veldhuyzen van Zanten emphatically replied "Oh, yes" and continued with the takeoff.

Collision

According to the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), the Pan Am captain said, "There he is!", when he spotted the KLM's landing lights through the fog just as his plane approached exit C-4. When it became clear that the KLM aircraft was approaching at takeoff speed, captain Grubbs exclaimed, "Goddamn, that son-of-a-bitch is coming!", while first officer Robert Bragg yelled, "Get off! Get off! Get off!". Captain Grubbs applied full power to the throttles and made a sharp left turn towards the grass in an attempt to avoid the impending collision. By the time the KLM pilots saw the Pan Am aircraft, they were already traveling too fast to stop. In desperation, the pilots prematurely rotated the aircraft and attempted to clear the Pan Am by lifting off, causing a severe tailstrike for 22 m (72 ft).

The KLM 747 was within 100 m (330 ft) of the Pan Am and moving at approximately 140 knots (260 km/h; 160 mph) when it left the ground. Its nose landing gear cleared the Pan Am, but its left-side engines, lower fuselage, and main landing gear struck the upper right side of the Pan Am's fuselage, ripping apart the center of the Pan Am jet almost directly above the wing. The right-side engines crashed through the Pan Am's upper deck immediately behind the cockpit.

The KLM plane remained briefly airborne, but the impact had sheared off the outer left engine, caused significant amounts of shredded materials to be ingested by the inner left engine, and damaged the wings. The plane immediately went into a stall, rolled sharply, and hit the ground approximately 150 m (500 ft) past the collision, sliding down the runway for a further 300 m (1,000 ft). The full load of fuel, which had caused the earlier delay, ignited immediately into a fireball that could not be subdued for several hours.

One of the 61 survivors of the Pan Am flight, John Coombs of Haleiwa, Hawaii, said that sitting in the nose of the plane probably saved his life: "We all settled back, and the next thing an explosion took place and the whole port side, left side of the plane, was just torn wide open."

Both airplanes were destroyed in the collision. All 248 passengers and crew aboard the KLM plane died, as did 335 passengers and crew aboard the Pan Am plane, primarily due to the fire and explosions resulting from the fuel spilled and ignited in the impact. The other 61 passengers and crew aboard the Pan Am aircraft survived, including the captain, first officer, and flight engineer. Most of the survivors on the Pan Am walked out onto the intact left wing, the side away from the collision, through holes in the fuselage structure. The Pan Am's engines were still running for a few minutes after the accident despite first officer Bragg's intention to turn them off. The top part of the cockpit, where the engine switches were located, had been destroyed in the collision, and all control lines were severed, leaving no method for the flight crew to control the aircraft's systems. Survivors waited for rescue, but it did not come promptly, as the firefighters were initially unaware that there were two aircraft involved and were concentrating on the KLM wreck hundreds of meters away in the thick fog and smoke. Eventually, most of the survivors on the wing dropped to the ground below.

Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten was KLM's chief of flight training and one of their most senior pilots. He had given the co-pilot on Flight 4805 his Boeing 747 qualification check about two months before the accident. His photograph was used for publicity materials such as magazine advertisements, including the inflight magazine on board PH-BUF. Before realising that Veldhuyzen van Zanten was the KLM captain who had been killed in the accident, KLM suggested that he should help with the investigation.

Aftermath

The following day, the Canary Islands Independence Movement, responsible for the bombing at Gran Canaria that started the chain of events that led to the disaster, denied responsibility for the accident.

Los Rodeos airport, the only operating airport on Tenerife in 1977, was closed to all fixed-wing traffic for two days. The first crash investigators to arrive at Tenerife the day after the crash travelled there by way of a three-hour boat ride from Las Palmas. The first aircraft that was able to land was a United States Air Force C-130 transport, which landed on the airport's main taxiway at 12:50 on March 29. The C-130 transport was arranged by Lt. Col Dr. James K. Slaton, who arrived before the crash investigators and started triaging surviving passengers. Slaton was dispatched from Torrejon Air Base just outside of Madrid, Spain. Slaton, who was a flight surgeon attached to the 613th Tactical Fighter Squadron, worked with the local medical staff and remained on scene until the last survivor was air lifted to awaiting medical facilities. The C-130 transported all surviving and injured passengers from Tenerife to Las Palmas; many of the injured were taken from there to Air Force bases in the United States for further treatment.

Spanish Army soldiers were tasked with clearing crash wreckage from the runways and taxiways. By March 30, a small plane shuttle service was approved, but large jets still could not land. Los Rodeos was fully reopened on April 3, after wreckage had been fully removed and engineers had repaired the airport's runway.

Investigation

The accident was investigated by Spain's Comisión de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación Civil (CIAIAC). About 70 personnel were involved in the investigation, including representatives from the Netherlands, the United States, and the two airline companies. Facts showed that there had been misinterpretations and false assumptions before the accident. Analysis of the CVR transcript showed that the KLM pilot thought that that he had been cleared for takeoff, while the Tenerife control tower believed that the KLM 747 was stationary at the end of the runway, awaiting takeoff clearance. It appears that KLM's co-pilot was not as certain about take-off clearance as the captain.

<snip>

Legacy of the disaster

As a consequence of the accident, sweeping changes were made to international airline regulations and to aircraft. Aviation authorities around the world introduced requirements for standard phrases and a greater emphasis on English as a common working language.

Air traffic instruction should not be acknowledged solely with a colloquial phrase such as "OK" or even "Roger" (which simply means the last transmission was received), but with a readback of the key parts of the instruction, to show mutual understanding. The phrase "take off" is now spoken only when the actual takeoff clearance is given or when cancelling that same clearance (i.e. "cleared for take-off" or "cancel take-off clearance" . Up until that point, aircrew and controllers should use the phrase "departure" in its place, e.g. "ready for departure". Additionally, an ATC clearance given to an aircraft already lined-up on the runway must be prefixed with the instruction "hold position".

. Up until that point, aircrew and controllers should use the phrase "departure" in its place, e.g. "ready for departure". Additionally, an ATC clearance given to an aircraft already lined-up on the runway must be prefixed with the instruction "hold position".

Cockpit procedures were also changed. Hierarchical relations among crew members were played down. More emphasis was placed on team decision-making by mutual agreement. Less experienced flight crew members were encouraged to challenge their captains when they believed something was not correct, and captains were instructed to listen to their crew and evaluate all decisions in light of crew concerns. This concept was later expanded into what is known today as crew resource management (CRM), training which is now mandatory for all airline pilots.

In 1978, a second airport on the island was opened: the new Tenerife–South Airport (TFS). This airport now serves the majority of international tourist flights. Los Rodeos, renamed to Tenerife North Airport (TFN), was then used only for domestic and inter-island flights. In 2002, a new terminal was opened and Tenerife North once again carries international traffic.

The Spanish government installed a ground radar at Tenerife North Airport following the accident.

</snip>

On March 27, 1977, two Boeing 747 passenger jets, KLM Flight 4805 and Pan Am Flight 1736, collided on the runway at Los Rodeos Airport (now Tenerife North Airport), on the Spanish island of Tenerife, Canary Islands, killing 583 people, making it the deadliest accident in aviation history.

A terrorist incident at Gran Canaria Airport had caused many flights to be diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two aircraft involved in the accident. The airport quickly became congested with parked airplanes blocking the only taxiway and forcing departing aircraft to taxi on the runway instead. Patches of thick fog were drifting across the airfield, so that the aircraft and control tower were unable to see one another.

The collision occurred when the KLM airliner initiated its takeoff run while the Pan Am airliner, shrouded in fog, was still on the runway and about to turn off onto the taxiway. The impact and resulting fire killed everyone on board KLM 4805 and most of the occupants of Pan Am 1736, with only 61 survivors in the front section of the aircraft.

The subsequent investigation by Spanish authorities concluded that the primary cause of the accident was the KLM captain's decision to take off in the mistaken belief that a takeoff clearance from air traffic control (ATC) had been issued. Dutch investigators placed a greater emphasis on mutual misunderstanding in radio communications between the KLM crew and ATC, but ultimately KLM admitted that their crew was responsible for the accident and the airline agreed to financially compensate the relatives of all of the victims.

The disaster had a lasting influence on the industry, highlighting in particular the vital importance of using standardized phraseology in radio communications. Cockpit procedures were also reviewed, contributing to the establishment of crew resource management as a fundamental part of airline pilots' training.

<snip>

Disaster

Diversion of aircraft to Los Rodeos

Both flights had been routine until they approached the islands. At 13:15, a bomb planted by the separatist Canary Islands Independence Movement exploded in the terminal of Gran Canaria International Airport, injuring eight people. There had been a phone call warning of the bomb, and another call received soon afterwards made claims of a second bomb at the airport. The civil aviation authorities had therefore closed the airport temporarily after the explosion, and all incoming flights bound for Gran Canaria had been diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two Boeing 747 aircraft involved in the disaster. The Pan Am crew indicated that they would prefer to circle in a holding pattern until landing clearance was given, but they were ordered to divert to Tenerife.

Los Rodeos was a regional airport that could not easily accommodate all of the traffic diverted from Gran Canaria, which included five large airliners. The airport had only one runway and one major taxiway running parallel to it, with four short taxiways connecting the two. While waiting for Gran Canaria airport to reopen, the diverted airplanes took up so much space that they were having to park on the long taxiway, making it unavailable for the purpose of taxiing. Instead, departing aircraft needed to taxi along the runway to position themselves for takeoff, a procedure known as a backtaxi or backtrack.

The authorities reopened Gran Canaria airport once the bomb threat had been contained. The Pan Am plane was ready to depart from Tenerife, but access to the runway was being obstructed by the KLM plane and a refueling vehicle; the KLM captain had decided to fully refuel at Los Rodeos instead of Las Palmas, apparently to save time. The Pan Am aircraft was unable to maneuver around the refueling KLM, in order to reach the runway for takeoff, due to a lack of safe clearance between the two planes, which was just 3.7 meters (12 ft). The refueling took about 35 minutes, after which the passengers were brought back to the aircraft. The search for a missing Dutch family of four, who had not returned to the waiting KLM plane, delayed the flight even further. A tour guide had chosen not to reboard for the flight to Las Palmas, because she lived on Tenerife and thought it impractical to fly to Gran Canaria only to return to Tenerife the next day. She was therefore not on the KLM plane when the accident happened, and she would be the only survivor of those who flew from Amsterdam to Tenerife on Flight 4805.

Taxiing and takeoff preparations

The tower instructed the KLM to taxi down the entire length of the runway and then make a 180-degree turn to get into takeoff position. While the KLM was backtaxiing on the runway, the controller asked the flight crew to report when it was ready to copy the ATC clearance. Because the flight crew was performing the checklist, copying this clearance was postponed until the aircraft was in takeoff position on Runway 30.

Simplified map of runway, taxiways, and aircraft. The red star indicates the location of impact. Not to scale.

Shortly afterward, the Pan Am was instructed to follow the KLM down the same runway, exit it by taking the third exit on their left and then use the parallel taxiway. Initially, the crew was unclear as to whether the controller had told them to take the first or third exit. The crew asked for clarification and the controller responded emphatically by replying: "The third one, sir; one, two, three; third, third one." The crew began the taxi and proceeded to identify the unmarked taxiways using an airport diagram as they reached them.

The crew successfully identified the first two taxiways (C-1 and C-2), but their discussion in the cockpit never indicated that they had sighted the third taxiway (C-3), which they had been instructed to use. There were no markings or signs to identify the runway exits and they were in conditions of poor visibility. The Pan Am crew appeared to remain unsure of their position on the runway until the collision, which occurred near the intersection with the fourth taxiway (C-4).

The angle of the third taxiway would have required the plane to perform a 148-degree turn, which would lead back toward the still-crowded main apron. At the end of C-3, the Pan Am would have to make another 148-degree turn, in order to continue taxiing towards the start of the runway, similar to a mirrored letter "Z". Taxiway C-4 would have required two 35-degree-turns. A study carried out by the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) after the accident concluded that making the second 148-degree turn at the end of taxiway C-3 would have been "a practical impossibility." The official report from the Spanish authorities explains that the controller instructed the Pan Am aircraft to use the third taxiway because this was the earliest exit that they could take to reach the unobstructed section of the parallel taxiway.

Weather conditions at Los Rodeos

Los Rodeos airport is at 633 meters (2,077 ft) above sea level, which gives rise to cloud behavior that differs from that at many other airports. Clouds at 600 m (2,000 ft) above ground level at the nearby coast are at ground level at Los Rodeos. Drifting clouds of different densities cause wildly varying visibilities, from unhindered at one moment to below the minimums the next. The collision took place in a high-density cloud.

The Pan Am crew found themselves in poor and rapidly deteriorating visibility almost as soon as they entered the runway. According to the ALPA report, as the Pan Am aircraft taxied to the runway, the visibility was about 500 m (1,600 ft). Shortly after they turned onto the runway it decreased to less than 100 m (330 ft).

Meanwhile, the KLM plane was still in good visibility, but with clouds blowing down the runway towards them. The aircraft completed its 180-degree turn in relatively clear weather and lined up on Runway 30. The next cloud was 900 m (3,000 ft) down the runway and moving towards the aircraft at about 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h).

Communication misunderstandings

Immediately after lining up, the KLM captain advanced the throttles and the aircraft started to move forward. First officer Meurs advised him that ATC clearance had not yet been given, and captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten responded: "No, I know that. Go ahead, ask." Meurs then radioed the tower that they were "ready for takeoff" and "waiting for our ATC clearance". The KLM crew then received instructions that specified the route that the aircraft was to follow after takeoff. The instructions used the word "takeoff," but did not include an explicit statement that they were cleared for takeoff.

Meurs read the flight clearance back to the controller, completing the readback with the statement: "We are now at takeoff." Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten interrupted the co-pilot's read-back with the comment, "We're going."

The controller, who could not see the runway due to the fog, initially responded with "OK" (terminology that is nonstandard), which reinforced the KLM captain's misinterpretation that they had takeoff clearance. The controller's response of "OK" to the co-pilot's nonstandard statement that they were "now at takeoff" was likely due to his misinterpretation that they were in takeoff position and ready to begin the roll when takeoff clearance was received, but not in the process of taking off. The controller then immediately added "stand by for takeoff, I will call you", indicating that he had not intended the clearance to be interpreted as a takeoff clearance.

A simultaneous radio call from the Pan Am crew caused mutual interference on the radio frequency, which was audible in the KLM cockpit as a 3-second-long shrill sound, (or heterodyne). This caused the KLM crew to miss the crucial latter portion of the tower's response. The Pan Am crew's transmission was "We're still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736!" This message was also blocked by the interference and inaudible to the KLM crew. Either message, if heard in the KLM cockpit, would have alerted the crew to the situation and given them time to abort the takeoff attempt.

Due to the fog, neither crew was able to see the other plane on the runway ahead of them. In addition, neither of the aircraft could be seen from the control tower, and the airport was not equipped with ground radar.

After the KLM plane had started its takeoff roll, the tower instructed the Pan Am crew to "report when runway clear." The Pan Am crew replied: "OK, will report when we're clear." On hearing this, the KLM flight engineer expressed his concern about the Pan Am not being clear of the runway by asking the pilots in his own cockpit, "Is he not clear, that Pan American?" Veldhuyzen van Zanten emphatically replied "Oh, yes" and continued with the takeoff.

Collision

According to the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), the Pan Am captain said, "There he is!", when he spotted the KLM's landing lights through the fog just as his plane approached exit C-4. When it became clear that the KLM aircraft was approaching at takeoff speed, captain Grubbs exclaimed, "Goddamn, that son-of-a-bitch is coming!", while first officer Robert Bragg yelled, "Get off! Get off! Get off!". Captain Grubbs applied full power to the throttles and made a sharp left turn towards the grass in an attempt to avoid the impending collision. By the time the KLM pilots saw the Pan Am aircraft, they were already traveling too fast to stop. In desperation, the pilots prematurely rotated the aircraft and attempted to clear the Pan Am by lifting off, causing a severe tailstrike for 22 m (72 ft).

The KLM 747 was within 100 m (330 ft) of the Pan Am and moving at approximately 140 knots (260 km/h; 160 mph) when it left the ground. Its nose landing gear cleared the Pan Am, but its left-side engines, lower fuselage, and main landing gear struck the upper right side of the Pan Am's fuselage, ripping apart the center of the Pan Am jet almost directly above the wing. The right-side engines crashed through the Pan Am's upper deck immediately behind the cockpit.

The KLM plane remained briefly airborne, but the impact had sheared off the outer left engine, caused significant amounts of shredded materials to be ingested by the inner left engine, and damaged the wings. The plane immediately went into a stall, rolled sharply, and hit the ground approximately 150 m (500 ft) past the collision, sliding down the runway for a further 300 m (1,000 ft). The full load of fuel, which had caused the earlier delay, ignited immediately into a fireball that could not be subdued for several hours.

One of the 61 survivors of the Pan Am flight, John Coombs of Haleiwa, Hawaii, said that sitting in the nose of the plane probably saved his life: "We all settled back, and the next thing an explosion took place and the whole port side, left side of the plane, was just torn wide open."

Both airplanes were destroyed in the collision. All 248 passengers and crew aboard the KLM plane died, as did 335 passengers and crew aboard the Pan Am plane, primarily due to the fire and explosions resulting from the fuel spilled and ignited in the impact. The other 61 passengers and crew aboard the Pan Am aircraft survived, including the captain, first officer, and flight engineer. Most of the survivors on the Pan Am walked out onto the intact left wing, the side away from the collision, through holes in the fuselage structure. The Pan Am's engines were still running for a few minutes after the accident despite first officer Bragg's intention to turn them off. The top part of the cockpit, where the engine switches were located, had been destroyed in the collision, and all control lines were severed, leaving no method for the flight crew to control the aircraft's systems. Survivors waited for rescue, but it did not come promptly, as the firefighters were initially unaware that there were two aircraft involved and were concentrating on the KLM wreck hundreds of meters away in the thick fog and smoke. Eventually, most of the survivors on the wing dropped to the ground below.

Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten was KLM's chief of flight training and one of their most senior pilots. He had given the co-pilot on Flight 4805 his Boeing 747 qualification check about two months before the accident. His photograph was used for publicity materials such as magazine advertisements, including the inflight magazine on board PH-BUF. Before realising that Veldhuyzen van Zanten was the KLM captain who had been killed in the accident, KLM suggested that he should help with the investigation.

Aftermath

The following day, the Canary Islands Independence Movement, responsible for the bombing at Gran Canaria that started the chain of events that led to the disaster, denied responsibility for the accident.

Los Rodeos airport, the only operating airport on Tenerife in 1977, was closed to all fixed-wing traffic for two days. The first crash investigators to arrive at Tenerife the day after the crash travelled there by way of a three-hour boat ride from Las Palmas. The first aircraft that was able to land was a United States Air Force C-130 transport, which landed on the airport's main taxiway at 12:50 on March 29. The C-130 transport was arranged by Lt. Col Dr. James K. Slaton, who arrived before the crash investigators and started triaging surviving passengers. Slaton was dispatched from Torrejon Air Base just outside of Madrid, Spain. Slaton, who was a flight surgeon attached to the 613th Tactical Fighter Squadron, worked with the local medical staff and remained on scene until the last survivor was air lifted to awaiting medical facilities. The C-130 transported all surviving and injured passengers from Tenerife to Las Palmas; many of the injured were taken from there to Air Force bases in the United States for further treatment.

Spanish Army soldiers were tasked with clearing crash wreckage from the runways and taxiways. By March 30, a small plane shuttle service was approved, but large jets still could not land. Los Rodeos was fully reopened on April 3, after wreckage had been fully removed and engineers had repaired the airport's runway.

Investigation

The accident was investigated by Spain's Comisión de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación Civil (CIAIAC). About 70 personnel were involved in the investigation, including representatives from the Netherlands, the United States, and the two airline companies. Facts showed that there had been misinterpretations and false assumptions before the accident. Analysis of the CVR transcript showed that the KLM pilot thought that that he had been cleared for takeoff, while the Tenerife control tower believed that the KLM 747 was stationary at the end of the runway, awaiting takeoff clearance. It appears that KLM's co-pilot was not as certain about take-off clearance as the captain.

<snip>

Legacy of the disaster

As a consequence of the accident, sweeping changes were made to international airline regulations and to aircraft. Aviation authorities around the world introduced requirements for standard phrases and a greater emphasis on English as a common working language.

Air traffic instruction should not be acknowledged solely with a colloquial phrase such as "OK" or even "Roger" (which simply means the last transmission was received), but with a readback of the key parts of the instruction, to show mutual understanding. The phrase "take off" is now spoken only when the actual takeoff clearance is given or when cancelling that same clearance (i.e. "cleared for take-off" or "cancel take-off clearance"

Cockpit procedures were also changed. Hierarchical relations among crew members were played down. More emphasis was placed on team decision-making by mutual agreement. Less experienced flight crew members were encouraged to challenge their captains when they believed something was not correct, and captains were instructed to listen to their crew and evaluate all decisions in light of crew concerns. This concept was later expanded into what is known today as crew resource management (CRM), training which is now mandatory for all airline pilots.

In 1978, a second airport on the island was opened: the new Tenerife–South Airport (TFS). This airport now serves the majority of international tourist flights. Los Rodeos, renamed to Tenerife North Airport (TFN), was then used only for domestic and inter-island flights. In 2002, a new terminal was opened and Tenerife North once again carries international traffic.

The Spanish government installed a ground radar at Tenerife North Airport following the accident.

</snip>

March 26, 2019

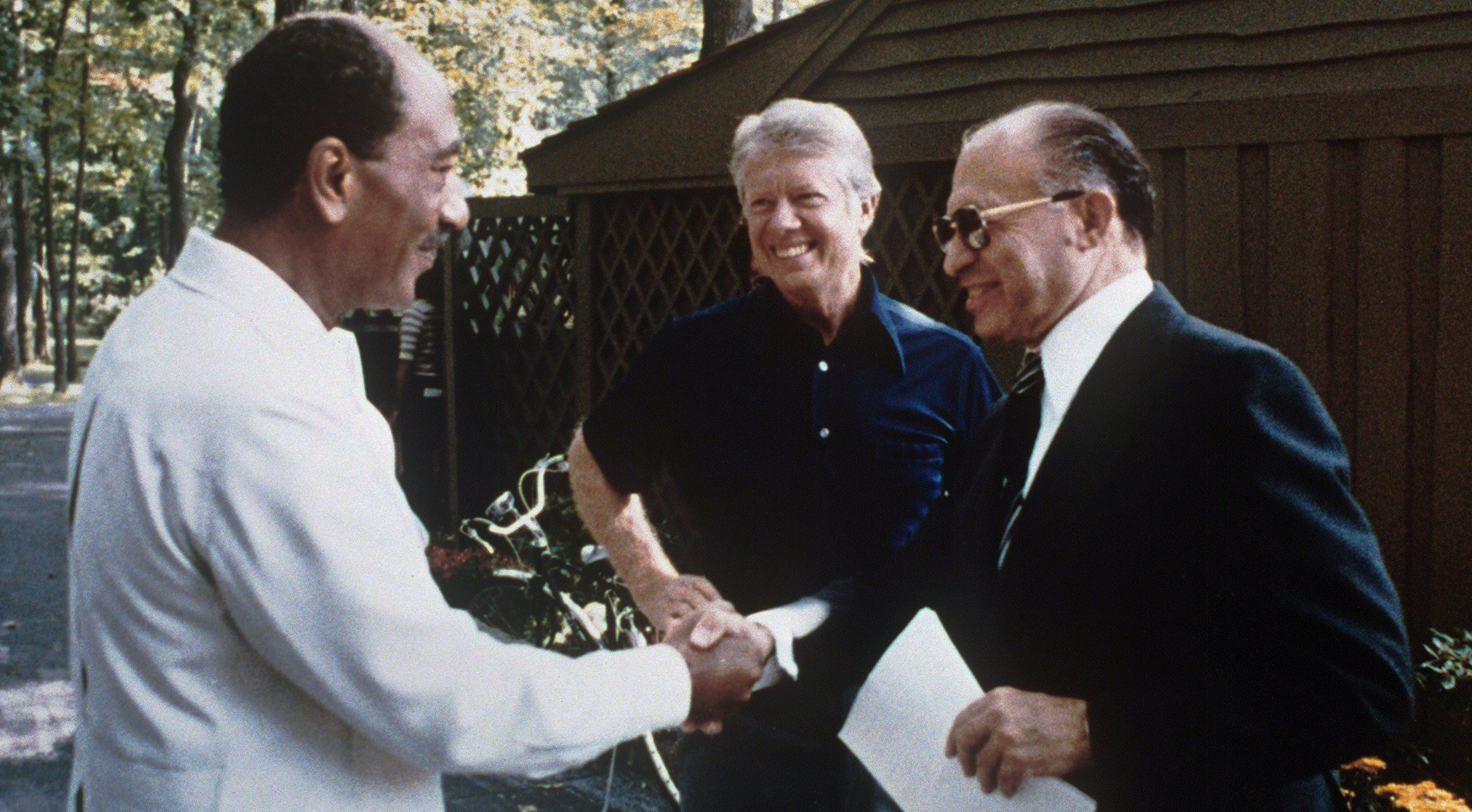

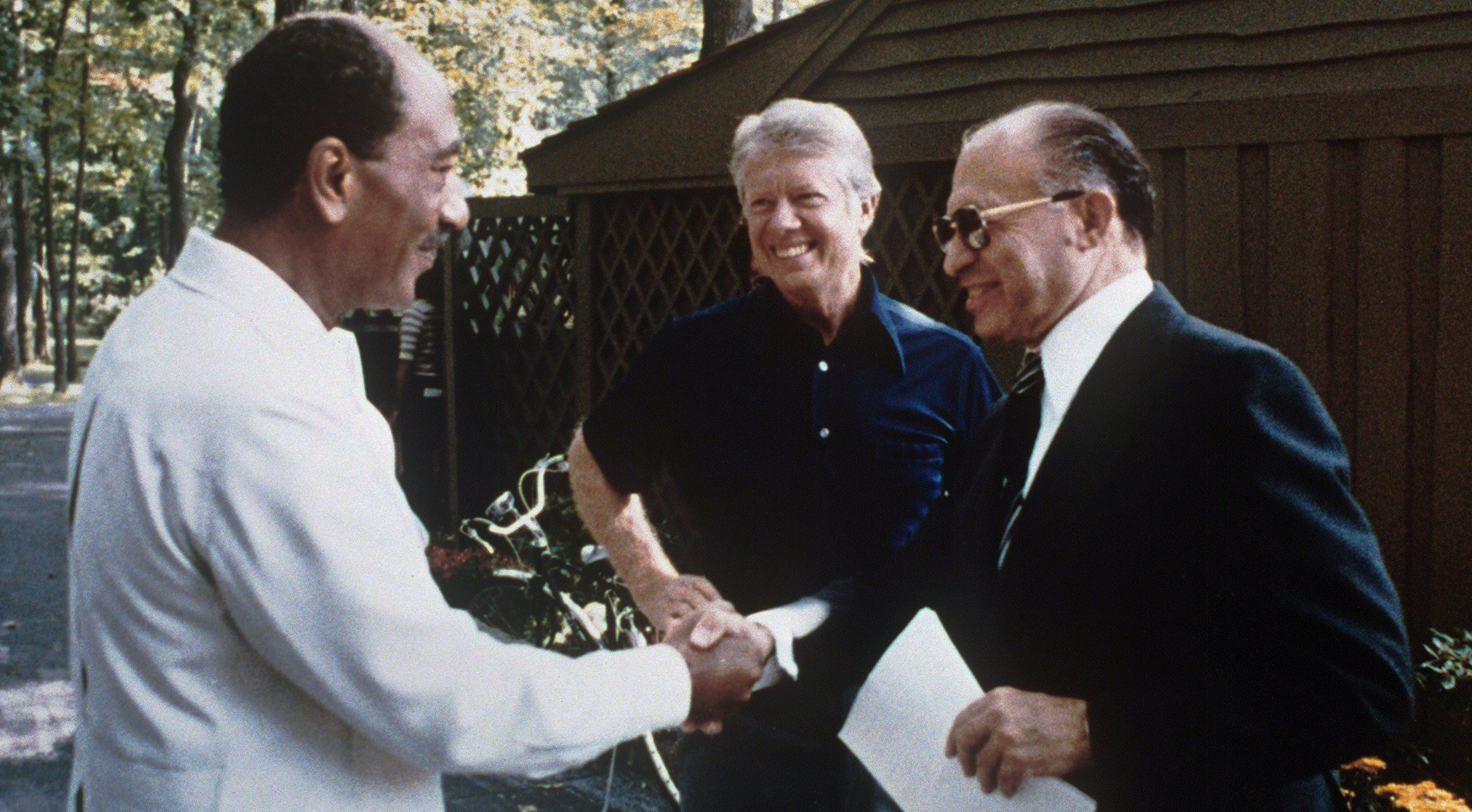

40 Years Ago Today; Sadat, Begin and Carter sign the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egypt%E2%80%93Israel_Peace_Treaty

The Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty (Arabic: معاهدة السلام المصرية الإسرائيلية?, Mu`āhadat as-Salām al-Misrīyah al-'Isrā'īlīyah; Hebrew: הסכם השלום בין ישראל למצרים?, Heskem HaShalom Bein Yisrael LeMitzrayim) was signed in Washington, D.C., United States on 26 March 1979, following the 1978 Camp David Accords. The Egypt–Israel treaty was signed by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin, and witnessed by United States president Jimmy Carter.

History

The peace treaty between Egypt and Israel was signed 16 months after Egyptian president Anwar Sadat's visit to Israel in 1977 after intense negotiation. The main features of the treaty were mutual recognition, cessation of the state of war that had existed since the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, normalization of relations and the complete withdrawal by Israel of its armed forces and civilians from the Sinai Peninsula which Israel had captured during the Six-Day War in 1967. Egypt agreed to leave the area demilitarized. The agreement also provided for the free passage of Israeli ships through the Suez Canal, and recognition of the Strait of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba as international waterways.

The agreement notably made Egypt the first Arab state to officially recognize Israel.

<snip>

International reaction