Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal

Dennis Donovan's Journal

May 18, 2021

Cross gently, Mr Grodin.

Charles Grodin, Familiar Face From TV and Film, Dies at 86

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/18/movies/charles-grodin-dead.html?smid=tw-nytimesarts&smtyp=cur

The actor Charles Grodin with the title dog in the hit 1992 family movie “Beethoven.”Credit...via Photofest

Mr. Grodin, who also appeared on Broadway in “Same Time, Next Year” and wrote books, was especially adept at deadpan comedy.

By Neil Genzlinger

May 18, 2021, 1:26 p.m. ET

Charles Grodin, the versatile actor familiar from “Same Time, Next Year” on Broadway, popular movies like “The Heartbreak Kid,” “Midnight Run” and “Beethoven” and numerous television appearances, died on Tuesday at his home in Wilton, Conn. He was 86.

His son, Nicholas, said the cause was bone marrow cancer.

With a great sense of deadpan comedy and the kind of Everyman good looks that lend themselves to playing businessmen or curmudgeonly fathers, Mr. Grodin found plenty of work as a supporting player and the occasional lead. He also had his own talk show for a time in the 1990s and was a frequent guest on the talk shows of others, making 36 appearances on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” and 17 on “Late Night With David Letterman.”

Mr. Grodin was a writer as well, with a number of plays and books to his credit. Though he never won a prestige acting award, he did win a writing Emmy for a 1977 Paul Simon television special, sharing it with Mr. Simon and six others.

-/snip-

The actor Charles Grodin with the title dog in the hit 1992 family movie “Beethoven.”Credit...via Photofest

Mr. Grodin, who also appeared on Broadway in “Same Time, Next Year” and wrote books, was especially adept at deadpan comedy.

By Neil Genzlinger

May 18, 2021, 1:26 p.m. ET

Charles Grodin, the versatile actor familiar from “Same Time, Next Year” on Broadway, popular movies like “The Heartbreak Kid,” “Midnight Run” and “Beethoven” and numerous television appearances, died on Tuesday at his home in Wilton, Conn. He was 86.

His son, Nicholas, said the cause was bone marrow cancer.

With a great sense of deadpan comedy and the kind of Everyman good looks that lend themselves to playing businessmen or curmudgeonly fathers, Mr. Grodin found plenty of work as a supporting player and the occasional lead. He also had his own talk show for a time in the 1990s and was a frequent guest on the talk shows of others, making 36 appearances on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” and 17 on “Late Night With David Letterman.”

Mr. Grodin was a writer as well, with a number of plays and books to his credit. Though he never won a prestige acting award, he did win a writing Emmy for a 1977 Paul Simon television special, sharing it with Mr. Simon and six others.

-/snip-

Cross gently, Mr Grodin.

May 17, 2021

BY TYLER BRIDGES | STAFF WRITER MAY 17, 2021 - 8:54 AM

Buddy Roemer, who rode a message of reform in the 1987 governor’s race to vault over three challengers and “slay the dragon” — scandal-torn three-time Gov. Edwin Edwards — but who lost reelection four years later to the same rival, died Monday in Baton Rouge.

Roemer was 77. He had been ill for months.

Roemer was a Democrat-turned-Republican, but he seemed too independent and headstrong to fit well in either party. He never followed the precept that to get ahead in politics, you had to get along with other politicians. With his sharp mind, he understood all the angles of a political play but disliked the deal-making that came with being governor. And that limited what he could achieve.

"He was all about reform, but it didn’t always work in his favor because of the realities of politics at the state Capitol," said Bernie Pinsonat, a veteran political consultant.

-/snip-

Buddy Roemer, Louisiana's former Democrat-turned-Republican governor, dies at 77

https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_4e8cd89e-3676-11eb-b2fc-eb5c23580375.html?8946789045BY TYLER BRIDGES | STAFF WRITER MAY 17, 2021 - 8:54 AM

Buddy Roemer, who rode a message of reform in the 1987 governor’s race to vault over three challengers and “slay the dragon” — scandal-torn three-time Gov. Edwin Edwards — but who lost reelection four years later to the same rival, died Monday in Baton Rouge.

Roemer was 77. He had been ill for months.

Roemer was a Democrat-turned-Republican, but he seemed too independent and headstrong to fit well in either party. He never followed the precept that to get ahead in politics, you had to get along with other politicians. With his sharp mind, he understood all the angles of a political play but disliked the deal-making that came with being governor. And that limited what he could achieve.

"He was all about reform, but it didn’t always work in his favor because of the realities of politics at the state Capitol," said Bernie Pinsonat, a veteran political consultant.

-/snip-

May 11, 2021

Cross gently, Norman.

Norman Lloyd Dies: 'St. Elsewhere' Actor Who Worked With Welles, Hitchcock & Chaplin Was 106

https://deadline.com/2021/05/norman-lloyd-dead-st-elsewhere-actor-1234754280/

Norman Lloyd on Monday, and in 1942's "Saboteur"

Courtesy photo; Everett

By Erik Pedersen

May 11, 2021 2:13pm

Norman Lloyd, the Emmy-nominated veteran actor, producer and director whose career ranged from Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre, Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur and acting with Charlie Chaplin in Limelight to St. Elsewhere, Dead Poets Society and The Practice, died May 10 in his sleep at his Los Angeles home. He was 106. A family friend confirmed the news to Deadline.

During one of the famous Lloyd birthday celebrations, Karl Malden said, ”Norman Lloyd is the history of our business.”

Blessed with a commanding voice, Lloyd’s acting career dates back to Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre troupe, of which he was the last surviving member. He was part of its first production — a modern-dress adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar on Broadway in 1937.

He originally was cast in Welles’ epic Citizen Kane and accompanied the director to Hollywood. When the filmmaker ran into his proverbial budget problems, Lloyd quit the project and retuned to New York, later making his screen debut as the villainous spy who fell from the top of the Statue of Liberty in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942).

-/snip-

Norman Lloyd on Monday, and in 1942's "Saboteur"

Courtesy photo; Everett

By Erik Pedersen

May 11, 2021 2:13pm

Norman Lloyd, the Emmy-nominated veteran actor, producer and director whose career ranged from Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre, Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur and acting with Charlie Chaplin in Limelight to St. Elsewhere, Dead Poets Society and The Practice, died May 10 in his sleep at his Los Angeles home. He was 106. A family friend confirmed the news to Deadline.

During one of the famous Lloyd birthday celebrations, Karl Malden said, ”Norman Lloyd is the history of our business.”

Blessed with a commanding voice, Lloyd’s acting career dates back to Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre troupe, of which he was the last surviving member. He was part of its first production — a modern-dress adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar on Broadway in 1937.

He originally was cast in Welles’ epic Citizen Kane and accompanied the director to Hollywood. When the filmmaker ran into his proverbial budget problems, Lloyd quit the project and retuned to New York, later making his screen debut as the villainous spy who fell from the top of the Statue of Liberty in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942).

-/snip-

Cross gently, Norman.

May 10, 2021

100 Years Ago Today; USS R-14 (Submarine) became a sailing ship and made her way home

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_R-14_(SS-91)

Seen here are the jury-rigged sails used to bring R-14 back to port in 1921; the mainsail rigged from the radio mast is the top sail in the photograph, and the mizzen made of eight blankets also is visible. R-14's acting commanding officer, Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas, USN, is at top left, without a hat.(Source: US Naval Historical Center).

USS R-14 (SS-91) was an R-class coastal and harbor defense submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down by the Fore River Shipbuilding Company, in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 6 November 1918. She was launched on 10 October 1919 sponsored by Ms. Florence L. Gardner and commissioned on 24 December 1919, with Lieutenant Vincent A. Clarke, Jr., in command.

After a shakedown cruise off the New England coast, R-14 moved to New London, Connecticut, where she prepared for transfer to the Pacific Fleet. In May, she headed south. Given hull classification symbol "SS-91" in July, she transited the Panama Canal in the same month and arrived at Pearl Harbor on 6 September. There, for the next nine years, she assisted in the development of submarine and anti-submarine warfare tactics, and participated in search and rescue operations.

R-14 — under acting command of Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas – ran out of usable fuel and lost radio communications in May 1921 while on a surface search mission for the seagoing tug Conestoga about 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) southeast of the island of Hawaii. Since the submarine's electric motors did not have enough battery power to propel her to Hawaii, the ship's engineering officer Roy Trent Gallemore came up with a novel solution to their problem. Lieutenant Gallemore decided they could try to sail the boat to the port of Hilo, Hawaii. He therefore ordered a foresail made of eight hammocks hung from a top boom made of pipe bunk frames lashed firmly together, all tied to the vertical kingpost of the torpedo loading crane forward of the submarine's superstructure. Seeing that this gave R-14 a speed of about 1 kn (1.2 mph; 1.9 km/h), as well as rudder control, he ordered a mainsail made of six blankets, hung from the sturdy radio mast (top sail in photo). This added .5 kn (0.58 mph; 0.93 km/h) to the speed. He then ordered a mizzen made of eight blankets hung from another top boom made of bunk frames, all tied to the vertically placed boom of the torpedo loading crane. This sail added another .5 kn (0.58 mph; 0.93 km/h). Around 12:30 pm on 12 May, Gallemore was able to begin charging the boat's batteries.] After 64 hours under sail at slightly varying speeds, R-14 entered Hilo Harbor under battery propulsion on the morning of 15 May 1921. Douglas received a letter of commendation for the crew's innovative actions from his Submarine Division Commander, CDR Chester W. Nimitz, USN.

-/snip-

Seen here are the jury-rigged sails used to bring R-14 back to port in 1921; the mainsail rigged from the radio mast is the top sail in the photograph, and the mizzen made of eight blankets also is visible. R-14's acting commanding officer, Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas, USN, is at top left, without a hat.(Source: US Naval Historical Center).

USS R-14 (SS-91) was an R-class coastal and harbor defense submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down by the Fore River Shipbuilding Company, in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 6 November 1918. She was launched on 10 October 1919 sponsored by Ms. Florence L. Gardner and commissioned on 24 December 1919, with Lieutenant Vincent A. Clarke, Jr., in command.

After a shakedown cruise off the New England coast, R-14 moved to New London, Connecticut, where she prepared for transfer to the Pacific Fleet. In May, she headed south. Given hull classification symbol "SS-91" in July, she transited the Panama Canal in the same month and arrived at Pearl Harbor on 6 September. There, for the next nine years, she assisted in the development of submarine and anti-submarine warfare tactics, and participated in search and rescue operations.

R-14 — under acting command of Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas – ran out of usable fuel and lost radio communications in May 1921 while on a surface search mission for the seagoing tug Conestoga about 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) southeast of the island of Hawaii. Since the submarine's electric motors did not have enough battery power to propel her to Hawaii, the ship's engineering officer Roy Trent Gallemore came up with a novel solution to their problem. Lieutenant Gallemore decided they could try to sail the boat to the port of Hilo, Hawaii. He therefore ordered a foresail made of eight hammocks hung from a top boom made of pipe bunk frames lashed firmly together, all tied to the vertical kingpost of the torpedo loading crane forward of the submarine's superstructure. Seeing that this gave R-14 a speed of about 1 kn (1.2 mph; 1.9 km/h), as well as rudder control, he ordered a mainsail made of six blankets, hung from the sturdy radio mast (top sail in photo). This added .5 kn (0.58 mph; 0.93 km/h) to the speed. He then ordered a mizzen made of eight blankets hung from another top boom made of bunk frames, all tied to the vertically placed boom of the torpedo loading crane. This sail added another .5 kn (0.58 mph; 0.93 km/h). Around 12:30 pm on 12 May, Gallemore was able to begin charging the boat's batteries.] After 64 hours under sail at slightly varying speeds, R-14 entered Hilo Harbor under battery propulsion on the morning of 15 May 1921. Douglas received a letter of commendation for the crew's innovative actions from his Submarine Division Commander, CDR Chester W. Nimitz, USN.

-/snip-

May 7, 2021

27 residents of Newark & Clifton Springs nursing homes test positive for COVID-19

https://www.rochesterfirst.com/news/local-news/27-residents-of-newark-clifton-springs-nursing-homes-test-positive-for-covid-19/

by: Ally Peters, Dan Gross, WROC Staff

Posted: May 7, 2021 / 04:05 PM EDT / Updated: May 7, 2021 / 04:13 PM EDT

NEWARK, N.Y. (WROC) — Dr. Robert Mayo, Chief Medical Officer of Rochester Regional Health announced on a Zoom press conference today that 27 residents between the DeMay Living Center in Newark, and Clifton Springs Nursing Home, have tested positive for COVID-19.

17 cases were reported at the DeMay facility, whereas 10 were reported from the other location.

https://twitter.com/allypetersnews/status/1390757002394099718

Dr. Mayo said that these cases were mainly identified through their regular testing, as 24 of the residents were asymptomatic, likely because they were previously vaccinated.

“The pandemic is still persisting, and it is really important to be vaccinated,” Dr. Mayo said.

One of the non vaccinated people have been hospitalized. Rochester Regional Health says it’s not clear how the virus was brought into the centers. They also don’t know if the cases were caused by a variant because that requires special testing.

-/snip-

by: Ally Peters, Dan Gross, WROC Staff

Posted: May 7, 2021 / 04:05 PM EDT / Updated: May 7, 2021 / 04:13 PM EDT

NEWARK, N.Y. (WROC) — Dr. Robert Mayo, Chief Medical Officer of Rochester Regional Health announced on a Zoom press conference today that 27 residents between the DeMay Living Center in Newark, and Clifton Springs Nursing Home, have tested positive for COVID-19.

17 cases were reported at the DeMay facility, whereas 10 were reported from the other location.

https://twitter.com/allypetersnews/status/1390757002394099718

Dr. Mayo said that these cases were mainly identified through their regular testing, as 24 of the residents were asymptomatic, likely because they were previously vaccinated.

“The pandemic is still persisting, and it is really important to be vaccinated,” Dr. Mayo said.

One of the non vaccinated people have been hospitalized. Rochester Regional Health says it’s not clear how the virus was brought into the centers. They also don’t know if the cases were caused by a variant because that requires special testing.

-/snip-

May 6, 2021

84 Years Ago Today; "Oh, the humanity!"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

The Hindenburg disaster occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at Naval Air Station Lakehurst. On board were 97 people (36 passengers and 61 crewmen); there were 36 fatalities (13 passengers and 22 crewmen, 1 worker on the ground).

The disaster was the subject of newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison's recorded radio eyewitness reports from the landing field, which were broadcast the next day. A variety of hypotheses have been put forward for both the cause of ignition and the initial fuel for the ensuing fire. The event shattered public confidence in the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airship and marked the abrupt end of the airship era.

Disaster

At 7:25 p.m. local time, the Hindenburg caught fire and quickly became engulfed in flames. Eyewitness statements disagree as to where the fire initially broke out; several witnesses on the port side saw yellow-red flames first jump forward of the top fin near the ventilation shaft of cells 4 and 5.[4] Other witnesses on the port side noted the fire actually began just ahead of the horizontal port fin, only then followed by flames in front of the upper fin. One, with views of the starboard side, saw flames beginning lower and farther aft, near cell 1 behind the rudders. Inside the airship, helmsman Helmut Lau, who was stationed in the lower fin, testified hearing a muffled detonation and looked up to see a bright reflection on the front bulkhead of gas cell 4, which "suddenly disappeared by the heat". As other gas cells started to catch fire, the fire spread more to the starboard side and the ship dropped rapidly. Although there were cameramen from four newsreel teams and at least one spectator known to be filming the landing, as well as numerous photographers at the scene, no known footage or photograph exists of the moment the fire started.

Wherever they started, the flames quickly spread forward first consuming cells 1 to 9, and the rear end of the structure imploded. Almost instantly, two tanks (it is disputed whether they contained water or fuel) burst out of the hull as a result of the shock of the blast. Buoyancy was lost on the stern of the ship, and the bow lurched upwards while the ship's back broke; the falling stern stayed in trim.

As the tail of the Hindenburg crashed into the ground, a burst of flame came out of the nose, killing 9 of the 12 crew members in the bow. There was still gas in the bow section of the ship, so it continued to point upward as the stern collapsed down. The cell behind the passenger decks ignited as the side collapsed inward, and the scarlet lettering reading "Hindenburg" was erased by flames as the bow descended. The airship's gondola wheel touched the ground, causing the bow to bounce up slightly as one final gas cell burned away. At this point, most of the fabric on the hull had also burned away and the bow finally crashed to the ground. Although the hydrogen had finished burning, the Hindenburg's diesel fuel burned for several more hours.

The fire bursts out of the nose of the Hindenburg, photographed by Murray Becker.

The time that it took from the first signs of disaster to the bow crashing to the ground is often reported as 32, 34 or 37 seconds. Since none of the newsreel cameras were filming the airship when the fire started, the time of the start can only be estimated from various eyewitness accounts and the duration of the longest footage of the crash. One careful analysis by NASA's Addison Bain gives the flame front spread rate across the fabric skin as about 49 ft/s (15 m/s) at some points during the crash, which would have resulted in a total destruction time of about 16 seconds (245m/15 m/s=16.3 s).

Some of the duralumin framework of the airship was salvaged and shipped back to Germany, where it was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when both were scrapped in 1940.

In the days after the disaster, an official board of inquiry was set up at Lakehurst to investigate the cause of the fire. The investigation by the US Commerce Department was headed by Colonel South Trimble Jr, while Dr. Hugo Eckener led the German commission.

The Hindenburg disaster occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at Naval Air Station Lakehurst. On board were 97 people (36 passengers and 61 crewmen); there were 36 fatalities (13 passengers and 22 crewmen, 1 worker on the ground).

The disaster was the subject of newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison's recorded radio eyewitness reports from the landing field, which were broadcast the next day. A variety of hypotheses have been put forward for both the cause of ignition and the initial fuel for the ensuing fire. The event shattered public confidence in the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airship and marked the abrupt end of the airship era.

Disaster

At 7:25 p.m. local time, the Hindenburg caught fire and quickly became engulfed in flames. Eyewitness statements disagree as to where the fire initially broke out; several witnesses on the port side saw yellow-red flames first jump forward of the top fin near the ventilation shaft of cells 4 and 5.[4] Other witnesses on the port side noted the fire actually began just ahead of the horizontal port fin, only then followed by flames in front of the upper fin. One, with views of the starboard side, saw flames beginning lower and farther aft, near cell 1 behind the rudders. Inside the airship, helmsman Helmut Lau, who was stationed in the lower fin, testified hearing a muffled detonation and looked up to see a bright reflection on the front bulkhead of gas cell 4, which "suddenly disappeared by the heat". As other gas cells started to catch fire, the fire spread more to the starboard side and the ship dropped rapidly. Although there were cameramen from four newsreel teams and at least one spectator known to be filming the landing, as well as numerous photographers at the scene, no known footage or photograph exists of the moment the fire started.

Wherever they started, the flames quickly spread forward first consuming cells 1 to 9, and the rear end of the structure imploded. Almost instantly, two tanks (it is disputed whether they contained water or fuel) burst out of the hull as a result of the shock of the blast. Buoyancy was lost on the stern of the ship, and the bow lurched upwards while the ship's back broke; the falling stern stayed in trim.

As the tail of the Hindenburg crashed into the ground, a burst of flame came out of the nose, killing 9 of the 12 crew members in the bow. There was still gas in the bow section of the ship, so it continued to point upward as the stern collapsed down. The cell behind the passenger decks ignited as the side collapsed inward, and the scarlet lettering reading "Hindenburg" was erased by flames as the bow descended. The airship's gondola wheel touched the ground, causing the bow to bounce up slightly as one final gas cell burned away. At this point, most of the fabric on the hull had also burned away and the bow finally crashed to the ground. Although the hydrogen had finished burning, the Hindenburg's diesel fuel burned for several more hours.

The fire bursts out of the nose of the Hindenburg, photographed by Murray Becker.

The time that it took from the first signs of disaster to the bow crashing to the ground is often reported as 32, 34 or 37 seconds. Since none of the newsreel cameras were filming the airship when the fire started, the time of the start can only be estimated from various eyewitness accounts and the duration of the longest footage of the crash. One careful analysis by NASA's Addison Bain gives the flame front spread rate across the fabric skin as about 49 ft/s (15 m/s) at some points during the crash, which would have resulted in a total destruction time of about 16 seconds (245m/15 m/s=16.3 s).

Some of the duralumin framework of the airship was salvaged and shipped back to Germany, where it was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when both were scrapped in 1940.

In the days after the disaster, an official board of inquiry was set up at Lakehurst to investigate the cause of the fire. The investigation by the US Commerce Department was headed by Colonel South Trimble Jr, while Dr. Hugo Eckener led the German commission.

May 4, 2021

51 years Ago Today; Tin soldiers and Nixon's coming...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kent_State_shootings

Mary Ann Vecchio gestures and screams as she kneels by the body of a student, Jeffrey Miller, lying face down on the campus of Kent State University, in Kent, Ohio.

The Kent State shootings, also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre, were the shootings on May 4, 1970, of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, during a mass protest against the bombing of Cambodia by United States military forces. Twenty-eight guardsmen fired approximately 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

Some of the students who were shot had been protesting against the Cambodian Campaign, which President Richard Nixon announced during a television address on April 30 of that year. Other students who were shot had been walking nearby or observing the protest from a distance.

There was a significant national response to the shootings: hundreds of universities, colleges, and high schools closed throughout the United States due to a student strike of 4 million students,[10] and the event further affected public opinion, at an already socially contentious time, over the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.

Timeline

Thursday, April 30

President Nixon announced that the "Cambodian Incursion" had been launched by United States combat forces.

Friday, May 1

At Kent State University, a demonstration with about 500 students was held on May 1 on the Commons (a grassy knoll in the center of campus traditionally used as a gathering place for rallies or protests). As the crowd dispersed to attend classes by 1 p.m., another rally was planned for May 4 to continue the protest of the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. There was widespread anger, and many protesters issued a call to "bring the war home". A group of history students buried a copy of the United States Constitution to symbolize that Nixon had killed it. A sign was put on a tree asking "Why is the ROTC building still standing?"

Trouble exploded in town around midnight, when people left a bar and began throwing beer bottles at police cars and breaking windows in downtown storefronts. In the process they broke a bank window, setting off an alarm. The news spread quickly and it resulted in several bars closing early to avoid trouble. Before long, more people had joined the vandalism.

By the time police arrived, a crowd of 120 had already gathered. Some people from the crowd lit a small bonfire in the street. The crowd appeared to be a mix of bikers, students, and transient people. A few members of the crowd began to throw beer bottles at the police, and then started yelling obscenities at them. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared a state of emergency, called the office of Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.

Saturday, May 2

City officials and downtown businesses received threats, and rumors proliferated that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and university. Several merchants reported that they were told that if they did not display anti-war slogans, their business would be burned down. Kent's police chief told the mayor that according to a reliable informant, the ROTC building, the local army recruiting station and post office had been targeted for destruction that night. There were rumors of students with caches of arms, plots to poison the local water supply with LSD, of students building underground tunnels for the purpose of blowing up the town's main store. Mayor Satrom met with Kent city officials and a representative of the Ohio Army National Guard. Following the meeting, Satrom made the decision to call Governor Rhodes and request that the National Guard be sent to Kent, a request that was granted. Because of the rumors and threats, Satrom believed that local officials would not be able to handle future disturbances. The decision to call in the National Guard was made at 5:00 p.m., but the guard did not arrive in town that evening until around 10 p.m. By this time, a large demonstration was under way on the campus, and the campus Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) building was burning. The arsonists were never apprehended, and no one was injured in the fire. According to the report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest:

Information developed by an FBI investigation of the ROTC building fire indicates that, of those who participated actively, a significant portion weren't Kent State students. There is also evidence to suggest that the burning was planned beforehand: railroad flares, a machete, and ice picks are not customarily carried to peaceful rallies.

There were reports that some Kent firemen and police officers were struck by rocks and other objects while attempting to extinguish the blaze. Several fire engine companies had to be called because protesters carried the fire hose into the Commons and slashed it. The National Guard made numerous arrests, mostly for curfew violations, and used tear gas; at least one student was slightly wounded with a bayonet.

Sunday, May 3

During a press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk, pounding which can be heard in the recording of his speech. He called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio.

We've seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we're going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We're not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They're worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They're the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus. I think that we're up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.

Rhodes also claimed he would obtain a court order declaring a state of emergency that would ban further demonstrations and gave the impression that a situation akin to martial law had been declared; however, he never attempted to obtain such an order.

During the day, some students came to downtown Kent to help with cleanup efforts after the rioting, actions which were met with mixed reactions from local businessmen. Mayor Satrom, under pressure from frightened citizens, ordered a curfew until further notice.

Around 8 p.m., another rally was held on the campus Commons. By 8:45 p.m., the Guardsmen used tear gas to disperse the crowd, and the students reassembled at the intersection of Lincoln and Main, holding a sit-in with the hopes of gaining a meeting with Mayor Satrom and University President Robert White. At 11:00 p.m., the Guard announced that a curfew had gone into effect and began forcing the students back to their dorms. A few students were bayoneted by Guardsmen.

Monday, May 4

On Monday, May 4, a protest was scheduled to be held at noon, as had been planned three days earlier. University officials attempted to ban the gathering, handing out 12,000 leaflets stating that the event was canceled. Despite these efforts, an estimated 2,000 people gathered on the university's Commons, near Taylor Hall. The protest began with the ringing of the campus's iron Victory Bell (which had historically been used to signal victories in football games) to mark the beginning of the rally, and the first protester began to speak.

Companies A and C, 1/145th Infantry and Troop G of the 2/107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard (ARNG), the units on the campus grounds, attempted to disperse the students. The legality of the dispersal was later debated at a subsequent wrongful death and injury trial. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that authorities did indeed have the right to disperse the crowd.

The dispersal process began late in the morning with campus patrolman Harold Rice riding in a National Guard Jeep, approaching the students to read an order to disperse or face arrest. The protesters responded by throwing rocks, striking one campus patrolman and forcing the Jeep to retreat.

Just before noon, the Guard returned and again ordered the crowd to disperse. When most of the crowd refused, the Guard used tear gas. Because of wind, the tear gas had little effect in dispersing the crowd, and some launched a second volley of rocks toward the Guard's line and chanted "Pigs off campus!" The students lobbed the tear gas canisters back at the National Guardsmen, who wore gas masks.

When it became clear that the crowd was not going to disperse, a group of 77 National Guard troops from A Company and Troop G, with bayonets fixed on their M1 Garand rifles, began to advance upon the hundreds of protesters. As the guardsmen advanced, the protesters retreated up and over Blanket Hill, heading out of the Commons area. Once over the hill, the students, in a loose group, moved northeast along the front of Taylor Hall, with some continuing toward a parking lot in front of Prentice Hall (slightly northeast of and perpendicular to Taylor Hall). The guardsmen pursued the protesters over the hill, but rather than veering left as the protesters had, they continued straight, heading toward an athletic practice field enclosed by a chain link fence. Here they remained for about 10 minutes, unsure of how to get out of the area short of retracing their path. During this time, the bulk of the students congregated to the left and front of the guardsmen, approximately 150 to 225 ft (46 to 69 m) away, on the veranda of Taylor Hall. Others were scattered between Taylor Hall and the Prentice Hall parking lot, while still others were standing in the parking lot, or dispersing through the lot as they had been previously ordered.

While on the practice field, the guardsmen generally faced the parking lot, which was about 100 yards (91 m) away. At one point, some of them knelt and aimed their weapons toward the parking lot, then stood up again. At one point the guardsmen formed a loose huddle and appeared to be talking to one another. They had cleared the protesters from the Commons area, and many students had left, but some stayed and were still angrily confronting the soldiers, some throwing rocks and tear gas canisters. About 10 minutes later, the guardsmen began to retrace their steps back up the hill toward the Commons area. Some of the students on the Taylor Hall veranda began to move slowly toward the soldiers as they passed over the top of the hill and headed back into the Commons.

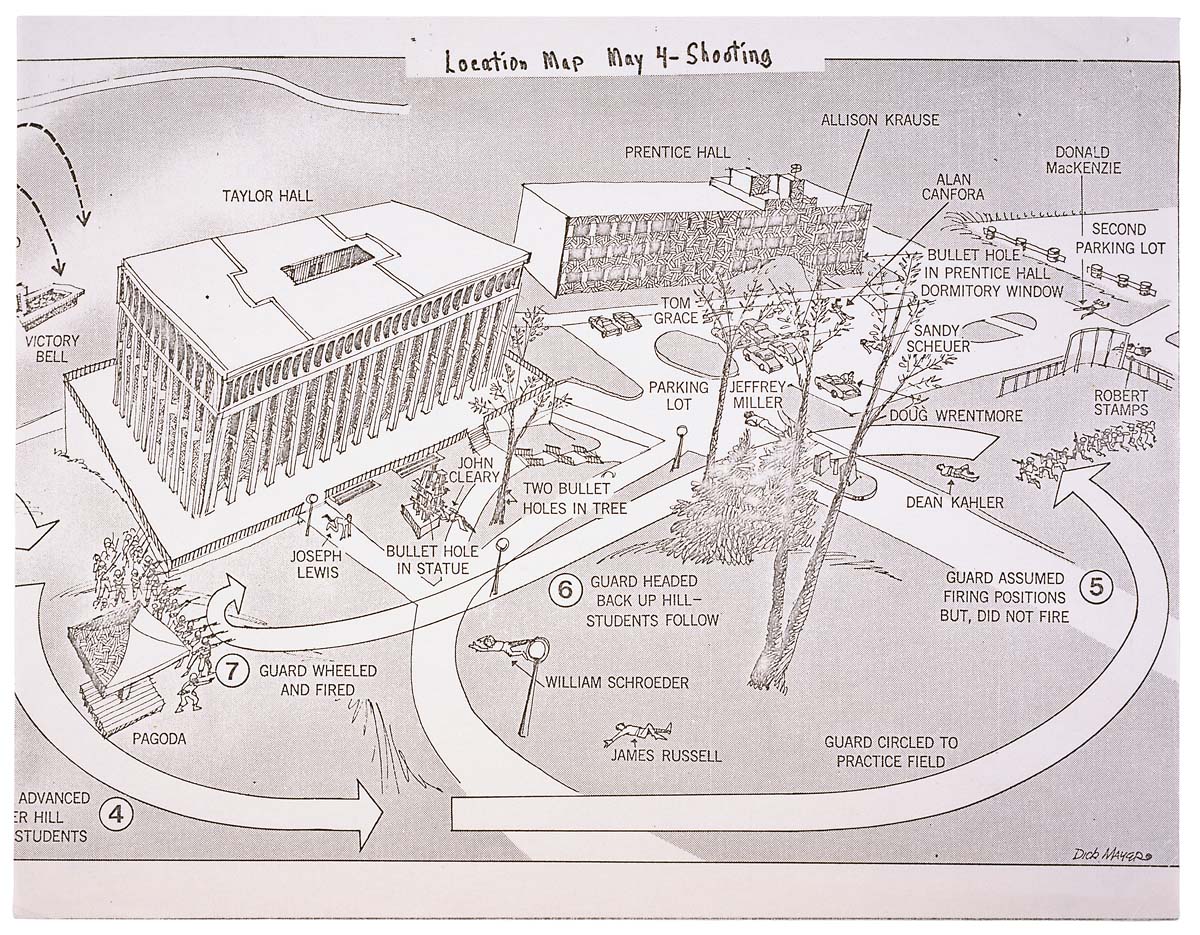

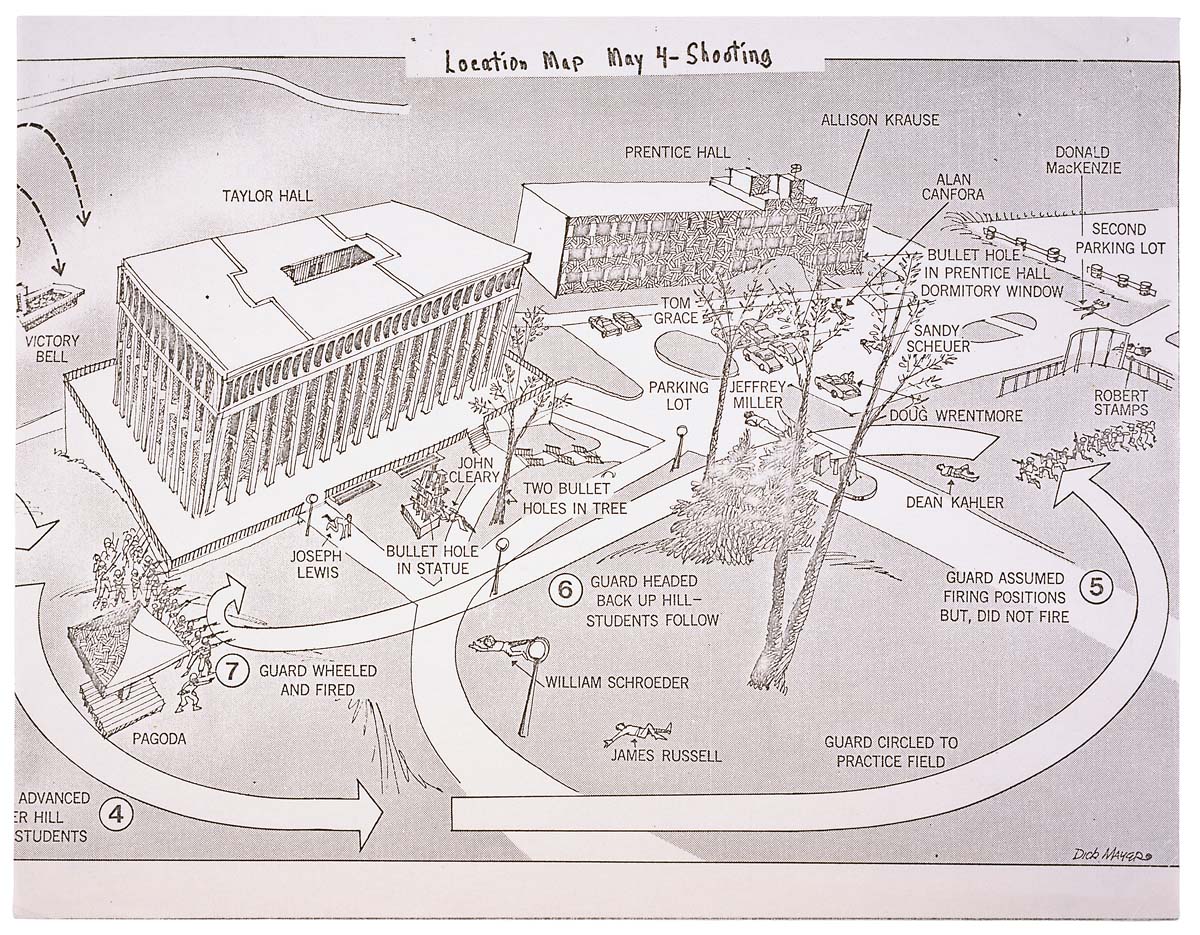

Map of the shootings

During their climb back to Blanket Hill, several guardsmen stopped and half-turned to keep their eyes on the students in the Prentice Hall parking lot. At 12:24 p.m., according to eyewitnesses, a sergeant named Myron Pryor turned and began firing at the crowd of students with his .45 pistol. A number of guardsmen nearest the students also turned and fired their rifles at the students. In all, at least 29 of the 77 guardsmen claimed to have fired their weapons, using an estimate of 67 rounds of ammunition. The shooting was determined to have lasted only 13 seconds, although John Kifner reported in The New York Times that "it appeared to go on, as a solid volley, for perhaps a full minute or a little longer." The question of why the shots were fired remains widely debated.

Photo taken from the perspective of where the Ohio National Guard soldiers stood when they opened fire on the students

Dent from a bullet in Solar Totem #1 sculpture by Don Drumm caused by a .30 caliber round fired by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State on May 4, 1970

The adjutant general of the Ohio National Guard told reporters that a sniper had fired on the guardsmen, which remains a debated allegation. Many guardsmen later testified that they were in fear for their lives, which was questioned partly because of the distance between them and the students killed or wounded. Time magazine later concluded that "triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State." The President's Commission on Campus Unrest avoided probing the question of why the shootings happened. Instead, it harshly criticized both the protesters and the Guardsmen, but it concluded that "the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable."

The shootings killed four students and wounded nine. Two of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, had participated in the protest. The other two, Sandra Scheuer and William Knox Schroeder, had been walking from one class to the next at the time of their deaths. Schroeder was also a member of the campus ROTC battalion. Of those wounded, none was closer than 71 feet (22 m) to the guardsmen. Of those killed, the nearest (Miller) was 265 feet (81 m) away, and their average distance from the guardsmen was 345 feet (105 m).

Eyewitness accounts

Several present related what they saw.

Unidentified speaker 1:

Unidentified speaker 2:

Another witness was Chrissie Hynde, the future lead singer of The Pretenders and a student at Kent State University at the time. In her 2015 autobiography she described what she saw:

Gerald Casale, the future bassist/singer of Devo, also witnessed the shootings. While speaking to the Vermont Review in 2005, he recalled what he saw:

Victims

Killed (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Wounded (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Memorial to Jeffrey Miller, taken from approximately the same perspective as John Filo's 1970 photograph, as it appeared in 2007.

Mary Ann Vecchio gestures and screams as she kneels by the body of a student, Jeffrey Miller, lying face down on the campus of Kent State University, in Kent, Ohio.

The Kent State shootings, also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre, were the shootings on May 4, 1970, of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, during a mass protest against the bombing of Cambodia by United States military forces. Twenty-eight guardsmen fired approximately 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

Some of the students who were shot had been protesting against the Cambodian Campaign, which President Richard Nixon announced during a television address on April 30 of that year. Other students who were shot had been walking nearby or observing the protest from a distance.

There was a significant national response to the shootings: hundreds of universities, colleges, and high schools closed throughout the United States due to a student strike of 4 million students,[10] and the event further affected public opinion, at an already socially contentious time, over the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.

Timeline

Thursday, April 30

President Nixon announced that the "Cambodian Incursion" had been launched by United States combat forces.

Friday, May 1

At Kent State University, a demonstration with about 500 students was held on May 1 on the Commons (a grassy knoll in the center of campus traditionally used as a gathering place for rallies or protests). As the crowd dispersed to attend classes by 1 p.m., another rally was planned for May 4 to continue the protest of the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. There was widespread anger, and many protesters issued a call to "bring the war home". A group of history students buried a copy of the United States Constitution to symbolize that Nixon had killed it. A sign was put on a tree asking "Why is the ROTC building still standing?"

Trouble exploded in town around midnight, when people left a bar and began throwing beer bottles at police cars and breaking windows in downtown storefronts. In the process they broke a bank window, setting off an alarm. The news spread quickly and it resulted in several bars closing early to avoid trouble. Before long, more people had joined the vandalism.

By the time police arrived, a crowd of 120 had already gathered. Some people from the crowd lit a small bonfire in the street. The crowd appeared to be a mix of bikers, students, and transient people. A few members of the crowd began to throw beer bottles at the police, and then started yelling obscenities at them. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared a state of emergency, called the office of Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.

Saturday, May 2

City officials and downtown businesses received threats, and rumors proliferated that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and university. Several merchants reported that they were told that if they did not display anti-war slogans, their business would be burned down. Kent's police chief told the mayor that according to a reliable informant, the ROTC building, the local army recruiting station and post office had been targeted for destruction that night. There were rumors of students with caches of arms, plots to poison the local water supply with LSD, of students building underground tunnels for the purpose of blowing up the town's main store. Mayor Satrom met with Kent city officials and a representative of the Ohio Army National Guard. Following the meeting, Satrom made the decision to call Governor Rhodes and request that the National Guard be sent to Kent, a request that was granted. Because of the rumors and threats, Satrom believed that local officials would not be able to handle future disturbances. The decision to call in the National Guard was made at 5:00 p.m., but the guard did not arrive in town that evening until around 10 p.m. By this time, a large demonstration was under way on the campus, and the campus Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) building was burning. The arsonists were never apprehended, and no one was injured in the fire. According to the report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest:

Information developed by an FBI investigation of the ROTC building fire indicates that, of those who participated actively, a significant portion weren't Kent State students. There is also evidence to suggest that the burning was planned beforehand: railroad flares, a machete, and ice picks are not customarily carried to peaceful rallies.

There were reports that some Kent firemen and police officers were struck by rocks and other objects while attempting to extinguish the blaze. Several fire engine companies had to be called because protesters carried the fire hose into the Commons and slashed it. The National Guard made numerous arrests, mostly for curfew violations, and used tear gas; at least one student was slightly wounded with a bayonet.

Sunday, May 3

During a press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk, pounding which can be heard in the recording of his speech. He called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio.

We've seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we're going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We're not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They're worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They're the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus. I think that we're up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.

Rhodes also claimed he would obtain a court order declaring a state of emergency that would ban further demonstrations and gave the impression that a situation akin to martial law had been declared; however, he never attempted to obtain such an order.

During the day, some students came to downtown Kent to help with cleanup efforts after the rioting, actions which were met with mixed reactions from local businessmen. Mayor Satrom, under pressure from frightened citizens, ordered a curfew until further notice.

Around 8 p.m., another rally was held on the campus Commons. By 8:45 p.m., the Guardsmen used tear gas to disperse the crowd, and the students reassembled at the intersection of Lincoln and Main, holding a sit-in with the hopes of gaining a meeting with Mayor Satrom and University President Robert White. At 11:00 p.m., the Guard announced that a curfew had gone into effect and began forcing the students back to their dorms. A few students were bayoneted by Guardsmen.

Monday, May 4

On Monday, May 4, a protest was scheduled to be held at noon, as had been planned three days earlier. University officials attempted to ban the gathering, handing out 12,000 leaflets stating that the event was canceled. Despite these efforts, an estimated 2,000 people gathered on the university's Commons, near Taylor Hall. The protest began with the ringing of the campus's iron Victory Bell (which had historically been used to signal victories in football games) to mark the beginning of the rally, and the first protester began to speak.

Companies A and C, 1/145th Infantry and Troop G of the 2/107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard (ARNG), the units on the campus grounds, attempted to disperse the students. The legality of the dispersal was later debated at a subsequent wrongful death and injury trial. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that authorities did indeed have the right to disperse the crowd.

The dispersal process began late in the morning with campus patrolman Harold Rice riding in a National Guard Jeep, approaching the students to read an order to disperse or face arrest. The protesters responded by throwing rocks, striking one campus patrolman and forcing the Jeep to retreat.

Just before noon, the Guard returned and again ordered the crowd to disperse. When most of the crowd refused, the Guard used tear gas. Because of wind, the tear gas had little effect in dispersing the crowd, and some launched a second volley of rocks toward the Guard's line and chanted "Pigs off campus!" The students lobbed the tear gas canisters back at the National Guardsmen, who wore gas masks.

When it became clear that the crowd was not going to disperse, a group of 77 National Guard troops from A Company and Troop G, with bayonets fixed on their M1 Garand rifles, began to advance upon the hundreds of protesters. As the guardsmen advanced, the protesters retreated up and over Blanket Hill, heading out of the Commons area. Once over the hill, the students, in a loose group, moved northeast along the front of Taylor Hall, with some continuing toward a parking lot in front of Prentice Hall (slightly northeast of and perpendicular to Taylor Hall). The guardsmen pursued the protesters over the hill, but rather than veering left as the protesters had, they continued straight, heading toward an athletic practice field enclosed by a chain link fence. Here they remained for about 10 minutes, unsure of how to get out of the area short of retracing their path. During this time, the bulk of the students congregated to the left and front of the guardsmen, approximately 150 to 225 ft (46 to 69 m) away, on the veranda of Taylor Hall. Others were scattered between Taylor Hall and the Prentice Hall parking lot, while still others were standing in the parking lot, or dispersing through the lot as they had been previously ordered.

While on the practice field, the guardsmen generally faced the parking lot, which was about 100 yards (91 m) away. At one point, some of them knelt and aimed their weapons toward the parking lot, then stood up again. At one point the guardsmen formed a loose huddle and appeared to be talking to one another. They had cleared the protesters from the Commons area, and many students had left, but some stayed and were still angrily confronting the soldiers, some throwing rocks and tear gas canisters. About 10 minutes later, the guardsmen began to retrace their steps back up the hill toward the Commons area. Some of the students on the Taylor Hall veranda began to move slowly toward the soldiers as they passed over the top of the hill and headed back into the Commons.

Map of the shootings

During their climb back to Blanket Hill, several guardsmen stopped and half-turned to keep their eyes on the students in the Prentice Hall parking lot. At 12:24 p.m., according to eyewitnesses, a sergeant named Myron Pryor turned and began firing at the crowd of students with his .45 pistol. A number of guardsmen nearest the students also turned and fired their rifles at the students. In all, at least 29 of the 77 guardsmen claimed to have fired their weapons, using an estimate of 67 rounds of ammunition. The shooting was determined to have lasted only 13 seconds, although John Kifner reported in The New York Times that "it appeared to go on, as a solid volley, for perhaps a full minute or a little longer." The question of why the shots were fired remains widely debated.

Photo taken from the perspective of where the Ohio National Guard soldiers stood when they opened fire on the students

Dent from a bullet in Solar Totem #1 sculpture by Don Drumm caused by a .30 caliber round fired by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State on May 4, 1970

The adjutant general of the Ohio National Guard told reporters that a sniper had fired on the guardsmen, which remains a debated allegation. Many guardsmen later testified that they were in fear for their lives, which was questioned partly because of the distance between them and the students killed or wounded. Time magazine later concluded that "triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State." The President's Commission on Campus Unrest avoided probing the question of why the shootings happened. Instead, it harshly criticized both the protesters and the Guardsmen, but it concluded that "the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable."

The shootings killed four students and wounded nine. Two of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, had participated in the protest. The other two, Sandra Scheuer and William Knox Schroeder, had been walking from one class to the next at the time of their deaths. Schroeder was also a member of the campus ROTC battalion. Of those wounded, none was closer than 71 feet (22 m) to the guardsmen. Of those killed, the nearest (Miller) was 265 feet (81 m) away, and their average distance from the guardsmen was 345 feet (105 m).

Eyewitness accounts

Several present related what they saw.

Unidentified speaker 1:

Suddenly, they turned around, got on their knees, as if they were ordered to, they did it all together, aimed. And personally, I was standing there saying, they're not going to shoot, they can't do that. If they are going to shoot, it's going to be blank.

Unidentified speaker 2:

The shots were definitely coming my way, because when a bullet passes your head, it makes a crack. I hit the ground behind the curve, looking over. I saw a student hit. He stumbled and fell, to where he was running towards the car. Another student tried to pull him behind the car, bullets were coming through the windows of the car.

As this student fell behind the car, I saw another student go down, next to the curb, on the far side of the automobile, maybe 25 or 30 yards from where I was lying. It was maybe 25, 30, 35 seconds of sporadic firing.

The firing stopped. I lay there maybe 10 or 15 seconds. I got up, I saw four or five students lying around the lot. By this time, it was like mass hysteria. Students were crying, they were screaming for ambulances. I heard some girl screaming, "They didn't have blank, they didn't have blank," no, they didn't.

Another witness was Chrissie Hynde, the future lead singer of The Pretenders and a student at Kent State University at the time. In her 2015 autobiography she described what she saw:

Then I heard the tatatatatatatatatat sound. I thought it was fireworks. An eerie sound fell over the common. The quiet felt like gravity pulling us to the ground. Then a young man's voice: "They fucking killed somebody!" Everything slowed down and the silence got heavier.

The ROTC building, now nothing more than a few inches of charcoal, was surrounded by National Guardsmen. They were all on one knee and pointing their rifles at ... us! Then they fired.

By the time I made my way to where I could see them it was still unclear what was going on. The guardsmen themselves looked stunned. We looked at them and they looked at us. They were just kids, 19 years old, like us. But in uniform. Like our boys in Vietnam.

Gerald Casale, the future bassist/singer of Devo, also witnessed the shootings. While speaking to the Vermont Review in 2005, he recalled what he saw:

All I can tell you is that it completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of two people I knew.

Two of the four people who were killed, Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause, were my friends. We were all running our asses off from these motherfuckers. It was total, utter bullshit. Live ammunition and gasmasks—none of us knew, none of us could have imagined ... They shot into a crowd that was running away from them!

I stopped being a hippie and I started to develop the idea of devolution. I got real, real pissed off.

Victims

Killed (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Jeffrey Glenn Miller; age 20; 265 ft (81 m) shot through the mouth; killed instantly

Allison B. Krause; age 19; 343 ft (105 m) fatal left chest wound; died later that day

William Knox Schroeder; age 19; 382 ft (116 m) fatal chest wound; died almost an hour later in a local hospital while undergoing surgery

Sandra Lee Scheuer; age 20; 390 ft (120 m) fatal neck wound; died a few minutes later from loss of blood

Wounded (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Joseph Lewis, Jr.; 71 ft (22 m); hit twice in the right abdomen and left lower leg

John R. Cleary; 110 ft (34 m); upper left chest wound

Thomas Mark Grace; 225 ft (69 m); struck in left ankle

Alan Michael Canfora; 225 ft (69 m); hit in his right wrist

Dean R. Kahler; 300 ft (91 m); back wound fracturing the vertebrae, permanently paralyzed from the chest down

Douglas Alan Wrentmore; 329 ft (100 m); hit in his right knee

James Dennis Russell; 375 ft (114 m); hit in his right thigh from a bullet and in the right forehead by birdshot, both wounds minor

Robert Follis Stamps; 495 ft (151 m); hit in his right buttock

Donald Scott MacKenzie; 750 ft (230 m); neck wound

Memorial to Jeffrey Miller, taken from approximately the same perspective as John Filo's 1970 photograph, as it appeared in 2007.

April 23, 2021

A huge explosion cracked house foundations in New Hampshire. An 'extreme' gender reveal party was to

https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/04/23/gender-reveal-explosion-new-hampshire-tannerite/

By

Andrea Salcedo

April 23, 2021 at 6:42 a.m. EDT

Sara and Matt Taglieri were enjoying dinner at their home in New Hampshire on Tuesday when a deafening blast knocked pictures off their walls and shook their house’s foundation. Their first thought was that there had been an accident at the concrete plant near their home.

They were partially right.

The massive explosion that rocked their Kingston, N.H., neighborhood and rattled nearby towns had come from a quarry by the plant, police said — but it had nothing to do with making concrete.

Instead, a man detonated 80 pounds of explosives as part of an elaborate gender-reveal party stunt, the Kingston Police Department told the New Hampshire Union Leader.

No injuries were reported, Kingston Police Chief Donald Briggs Jr. told the Union Leader, but the blast frightened neighbors, left nearby homes with cracks on their walls and appeared to turn the local tap water brown.

-/snip-

By

Andrea Salcedo

April 23, 2021 at 6:42 a.m. EDT

Sara and Matt Taglieri were enjoying dinner at their home in New Hampshire on Tuesday when a deafening blast knocked pictures off their walls and shook their house’s foundation. Their first thought was that there had been an accident at the concrete plant near their home.

They were partially right.

The massive explosion that rocked their Kingston, N.H., neighborhood and rattled nearby towns had come from a quarry by the plant, police said — but it had nothing to do with making concrete.

Instead, a man detonated 80 pounds of explosives as part of an elaborate gender-reveal party stunt, the Kingston Police Department told the New Hampshire Union Leader.

No injuries were reported, Kingston Police Chief Donald Briggs Jr. told the Union Leader, but the blast frightened neighbors, left nearby homes with cracks on their walls and appeared to turn the local tap water brown.

-/snip-

April 19, 2021

32 Years Ago Today; A Firing Exercise goes terribly wrong in Turret 2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Iowa_turret_explosion

Debris and smoke fly through the air as USS Iowa's Turret Two's center gun explodes

USS Iowa turret explosion

On 19 April 1989, the Number Two 16-inch gun turret of the United States Navy battleship USS Iowa (BB-61) exploded. The explosion in the center gun room killed 47 of the turret's crewmen and severely damaged the gun turret itself. Two major investigations were undertaken into the cause of the explosion, one by the U.S. Navy and then one by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and Sandia National Laboratories. The investigations produced conflicting conclusions.

The first investigation into the explosion, conducted by the U.S. Navy, concluded that one of the gun turret crew members, Clayton Hartwig, who died in the explosion, had deliberately caused it. During the investigation, numerous leaks to the media, later attributed to U.S. Navy officers and investigators, implied that Hartwig and another sailor, Kendall Truitt, had engaged in a homosexual relationship and that Hartwig had caused the explosion after their relationship had soured. In its report, however, the U.S. Navy concluded that the evidence did not show that Hartwig was homosexual but that he was suicidal and had caused the explosion with either an electronic or chemical detonator.

The victims' families, the media, and members of the U.S. Congress were sharply critical of the U.S. Navy's findings. The U.S. Senate and U.S. House Armed Services Committees both held hearings to inquire into the Navy's investigation and later released reports disputing the U.S. Navy's conclusions. The Senate committee asked the GAO to review the U.S. Navy's investigation. To assist the GAO, Sandia National Laboratories provided a team of scientists to review the Navy's technical investigation.

During its review, Sandia determined that a significant overram of the powder bags into the gun had occurred as it was being loaded and that the overram could have caused the explosion. A subsequent test by the Navy of the overram scenario confirmed that an overram could have caused an explosion in the gun breech. Sandia's technicians also found that the physical evidence did not support the U.S. Navy's theory that an electronic or chemical detonator had been used to initiate the explosion.

In response to the new findings, the U.S. Navy, with Sandia's assistance, reopened the investigation. In August 1991, Sandia and the GAO completed their reports, concluding that the explosion was likely caused by an accidental overram of powder bags into the breech of the 16-inch gun. The U.S. Navy, however, disagreed with Sandia's opinion and concluded that the cause of the explosion could not be determined. The U.S. Navy expressed regret (but did not offer apology) to Hartwig's family and closed its investigation.

Preparation for fleet exercise

On 10 April the battleship was visited by commander of the US 2nd Fleet, Vice Admiral Jerome L. Johnson, and on 13 April Iowa sailed from Norfolk to participate in a fleet exercise in the Caribbean Sea near Puerto Rico. The exercise, titled "FLEETEX 3-89", began on or around 17 April under Johnson's command. Iowa served as Johnson's flagship during the exercise.

Throughout the night of 18 April, Turret Two's crew conducted a major overhaul of their turret in preparation for a firing exercise scheduled to take place the next day. The center gun's compressed air system, which cleansed the bore of sparks and debris each time the gun was fired, was not operating properly.

Also on 18 April, Iowa's fire-control officer, Lieutenant Leo Walsh, conducted a briefing to discuss the next day's main battery exercise. Moosally, Morse, Kissinger, and Costigan did not attend the briefing. During the briefing, Skelley announced that Turret Two would participate in an experiment of his design in which D-846 powder would be used to fire 2700 lb (1224.7 kg) shells.

The powder lots of D-846 were among the oldest on board Iowa, dating back to 1943–1945, and were designed to fire 1900 lb (861.8 kg) shells. In fact, printed on each D-846 powder canister were the words, "WARNING: Do Not Use with 2,700-pound projectiles." D-846 powder burned faster than normal powder, which meant that it exerted greater pressure on the shell when fired. Skelley explained that the experiment's purpose was to improve the accuracy of the guns. Skelley's plan was for Turret Two to fire ten 2,700-pound practice (no explosives) projectiles, two from the left gun and four rounds each from the center and right guns. Each shot was to use five bags of D-846, instead of the six bags normally used, and to fire at the empty ocean 17 nautical miles (20 mi; 30 km) away.

Ziegler was especially concerned about his center gun crew. The rammerman, Robert W. Backherms, was inexperienced, as were the powder car operator, Gary J. Fisk, the primerman, Reginald L. Johnson Jr., and the gun captain, Richard Errick Lawrence. To help supervise Lawrence, Ziegler assigned Gunner's Mate Second Class Clayton Hartwig, the former center gun captain, who had been excused from gun turret duty because of a pending reassignment to a new duty station in London, to the center gun's crew for the firing exercise. Because of the late hour, Ziegler did not inform Hartwig of his assignment until the morning of 19 April, shortly before the firing exercise was scheduled to begin.

The rammerman's position was of special concern, as ramming was considered the most dangerous part of loading the gun. The ram was used to first thrust the projectile and then the powder bags into the gun's breech. The ram speed used for the projectile was much faster (14 feet (4.3 m) per second) than that used for the lighter powder bags (1.5 feet (0.46 m) per second), but there was no safety device on the ram piston to prevent the rammerman from accidentally pushing the powder bags at the faster speed. Overramming the powder bags into the gun could subject the highly flammable powder to excessive friction and compression, with a resulting increased danger of premature combustion. Also, if the bags were pushed too far into the gun, a gap between the last bag and the primer might prevent the powder from igniting when the gun was fired, causing a misfire. None of Iowa's rammermen had any training or experience in ramming nonstandard five-bag loads into the guns. Complicating the task, as the rammerman was shoving the powder bags, he was also supposed to simultaneously operate a lever to shut the powder hoist door and lower the powder hoist car. Iowa crewmen later stated that Turret Two's center gun rammer would sometimes "take off" uncontrollably on its own at high speed. Furthermore, Backherms had never operated the ram before during a live fire shoot.

Explosion

At 08:31 on 19 April, the main turret crewmembers were ordered to their stations in Turrets One, Two, and Three. Thirty minutes later the turrets reported that they were manned, swiveled to starboard in firing position, and ready to begin the drill. Vice Admiral Johnson and his staff entered the bridge to watch the firing exercise. Iowa was 260 nautical miles (300 mi; 480 km) northeast of Puerto Rico, steaming at 15 knots (17 mph; 28 km/h).

Turret One fired first, beginning at 09:33. Turret One's left gun misfired and its crew was unable to get the gun to discharge. Moosally ordered Turret Two to load and fire a three-gun salvo. According to standard procedure, the misfire in Turret One should have been resolved first before proceeding further with the exercise.

Forty-four seconds after Moosally's order, Lieutenant Buch reported that Turret Two's right gun was loaded and ready to fire. Seventeen seconds later, he reported that the left gun was ready. A few seconds later, Errick Lawrence, in Turret Two's center gun room, reported to Ziegler over the turret's phone circuit that, "We have a problem here. We are not ready yet. We have a problem here."[30] Ziegler responded by announcing over the turret's phone circuit, "Left gun loaded, good job. Center gun is having a little trouble. We'll straighten that out." Mortensen, monitoring Turret Two's phone circuit from his position in Turret One, heard Buch confirm that the left and right guns were loaded. Lawrence then called out, "I'm not ready yet! I'm not ready yet!" Next, Ernie Hanyecz, Turret Two's leading petty officer suddenly called out, "Mort! Mort! Mort!" Ziegler shouted, "Oh, my God! The powder is smoldering!"[34] At this time, Ziegler may have opened the door from the turret officer's booth in the rear of the turret into the center gun room and yelled at the crew to get the breech closed. About this same time, Hanyecz yelled over the phone circuit, "Oh, my God! There's a flash!"

Iowa's Number Two turret is cooled with sea water shortly after exploding.

At 09:53, about 81 seconds after Moosally's order to load and 20 seconds after the left gun had reported loaded and ready, Turret Two's center gun exploded. A fireball between 2,500 and 3,000 °F (1,400 and 1,600 °C) and traveling at 2,000 feet per second (610 m/s) with a pressure of 4,000 pounds-force per square inch (28 MPa) blew out from the center gun's open breech. The explosion caved in the door between the center gun room and the turret officer's booth and buckled the bulkheads separating the center gun room from the left and right gun rooms. The fireball spread through all three gun rooms and through much of the lower levels of the turret. The resulting fire released toxic gases, including cyanide gas from burning polyurethane foam, which filled the turret. Shortly after the initial explosion, the heat and fire ignited 2,000 pounds (910 kg) of powder bags in the powder-handling area of the turret. Nine minutes later, another explosion, most likely caused by a buildup of carbon monoxide gas, occurred. All 47 crewmen inside the turret were killed. The turret contained most of the force of the explosion. Twelve crewmen working in or near the turret's powder magazine and annular spaces, located adjacent to the bottom of the turret, were able to escape without serious injury. These men were protected by blast doors which separate the magazine spaces from the rest of the turret.

Immediate aftermath

Firefighting crews quickly responded and sprayed the roof of the turret and left and right gun barrels, which were still loaded, with water. Meyer and Kissinger, wearing gas masks, descended below decks and inspected the powder flats in the turret, noting that the metal walls of the turret flats surrounding several tons of unexploded powder bags in the turret were now "glowing a bright cherry red". Meyer and Kissinger were accompanied by Gunner's Mate Third Class Noah Melendez in their inspection of the turret. On Kissinger's recommendation, Moosally ordered Turret Two's magazines, annular spaces, and powder flats flooded with seawater, preventing the remaining powder from exploding. The turret fire was extinguished in about 90 minutes. Brian Scanio was the first fireman to enter the burning turret, followed soon after by Robert O. Shepherd, Ronald G. Robb, and Thad W. Harms. The firemen deployed hoses inside the turret.

After the fire was extinguished, Mortensen entered the turret to help identify the bodies of the dead crewmen. Mortensen found Hartwig's body, which he identified by a distinctive tattoo on the upper left arm, at the bottom of the 20-foot (6.1 m) deep center gun pit instead of in the gun room. His body was missing his lower forearms, legs below the knees, and was partially, but not badly, charred. The gas ejection air valve for the center gun was located at the bottom of the pit, leading Mortensen to believe that Hartwig had been sent into the pit to turn it on before the explosion occurred. Mortensen also found that the center gun's powder hoist had not been lowered, which was unusual since the hoist door was closed and locked.

Navy pallbearers, attended by an honor guard, carry the remains of one of the victims from the turret explosion after its arrival at Dover Air Force Base on 20 April 1989.

After most of the water was pumped out, the bodies in the turret were removed without noting or photographing their locations. The next day, the bodies were flown from the ship by helicopter to Roosevelt Roads Naval Station, Puerto Rico. From there, they were flown on a United States Air Force C-5 Galaxy transport aircraft to the Charles C. Carson Center for Mortuary Affairs at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware. Meyer made a rudimentary sketch of the locations of the bodies in the turret which would later contradict some of the findings in the U.S. Navy's initial investigation. With assistance from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the U.S. Navy was able to complete identification of all 47 sets of remains on 16 May 1989. Contradicting FBI records, the U.S. Navy would insist that all the remains had been identified by 24 April 1989, when all of the bodies were released to the families. The FBI cut the fingers off the unidentified corpses to identify them later. Body parts which had not been matched to torsos were discarded. Many of the remains were released to family members for burial before they were positively identified. Most of the bodies recovered from the center gun and turret officer's booth were badly burned and in pieces, making identification difficult. The bodies discovered lower in the turret were mostly intact; those crewmen had apparently died from suffocation, poisonous gases, or from impact trauma after being thrown around by the explosion. An explosive ordnance disposal technician, Operations Specialist First Class James Bennett Drake, from the nearby USS Coral Sea was sent to Iowa to assist in unloading the powder in Turret Two's left and right guns. After observing the scene in the center gun room and asking some questions, Drake told Iowa crewmen that, "It's my opinion that the explosion started in the center gun room caused by compressing the powder bags against the sixteen-inch shell too far and too fast with the rammer arm". Drake also helped Mortensen unload the powder from Turret One's left gun. When Turret One's left gun's breech was opened, it was discovered that the bottom powder bag was turned sideways. The projectile in Turret One's left gun was left in place and was eventually fired four months later.

Morse directed a cleanup crew, supervised by Lieutenant Commander Bob Holman, to make Turret Two "look as normal as possible". Over the next day, the crew swept, cleaned, and painted the inside of the turret. Loose or damaged equipment was tossed into the ocean. No attempt was made to record the locations or conditions of damaged equipment in the turret. "No one was preserving the evidence," said Brian R. Scanio, a fireman present at the scene.[46] A team of Naval Investigative Service (NIS) investigators (the predecessor of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service or NCIS) stationed nearby on the aircraft carrier Coral Sea was told that their services in investigating Iowa's mishap were not needed. At the same time, Moosally called a meeting with all of his officers, except Meyer, who was working in Turret One, in the ship's wardroom. At the meeting, Iowa's legal officer, Lieutenant Commander Richard Bagley, instructed the ship's officers on how to limit their testimony during the forthcoming investigation into the explosion. Terry McGinn, who was present at the meeting, stated later that Bagley "told everybody what to say. It was a party line pure and simple".

On 23 April Iowa returned to Norfolk, where a memorial service was held on 24 April. Several thousand people, including family members of many of the victims, attended the ceremony at which President George H. W. Bush spoke. During his speech, Bush stated, "I promise you today, we will find out 'why,' the circumstances of this tragedy." In a press conference after the ceremony, Moosally said that the two legalmen killed in the turret were assigned there as "observers". He also claimed that everyone in the turret was qualified for the position that they were filling.

Shortly after the memorial service at Norfolk on 24 April, Kendall Truitt told Hartwig's family that Hartwig had taken out a $50,000 double indemnity life insurance policy on himself and named Truitt as the sole beneficiary. Truitt was a friend of Hartwig's and had been working in Turret Two's powder magazine at the time of the explosion, but had escaped without serious injury. Truitt promised to give the life insurance money to Hartwig's parents. Unsure if she could trust Truitt, Kathy Kubicina, Hartwig's sister, mailed letters on 4 May to Moosally, Morse, Costigan, Iowa's Chaplain Lieutenant Commander James Danner, and to Ohio Senators Howard Metzenbaum and John Glenn in which she described the life insurance policy. She asked that someone talk to Truitt to convince him to give the money to Hartwig's parents.

Investigation conclusion

On 15 July 1989 Milligan submitted his completed report on the explosion to his chain of command. The 60-page report found that the explosion was a deliberate act "most probably" committed by Hartwig using an electronic timer. The report concluded that the powder bags had been overrammed into the center gun by 21 inches (53 cm), but had been done so under Hartwig's direction in order to trigger the explosive timer that he had placed between two of the powder bags.

Donnell, on 28 July, endorsed Milligan's report, saying that the determination that Hartwig had sabotaged the gun "leaves the reader incredulous, yet the opinion is supported by facts and analysis from which it flows logically and inevitably". Donnell's superior, Atlantic Fleet Commander Admiral Powell F. Carter, Jr., then endorsed the report, adding that the report showed that there were "substantial and serious failures by Moosally and Morse", and forwarded the report to the CNO, Carlisle Trost. Although Miceli had just announced that test results at Dahlgren showed that an electronic timer had not caused the explosion, Trost endorsed the report on 31 August, stating that Hartwig was "the individual who had motive, knowledge, and physical position within the turret gun room to place a device in the powder train". Trost's endorsement cited Smith's statement to the NIS as further evidence that Hartwig was the culprit. Milligan's report was not changed to reflect Miceli's new theory that a chemical igniter, not an electrical timer, had been used to initiate the explosion.