Latin America

Related: About this forumAmazonia and the World:A Threatened Realm of Life and Stories

MAY 28, 2023

BY JULIE WARK

Last surviving member of a tribe massacred by cattle ranchers in Amazonian state of Rondônia, Brazil. Photo: Acervo/Funai/

The rubber era was so violent that it lives on in the myths of Amazonian oral traditions. Daughters and granddaughters of women who were raped by rubber overseers are sometimes also raped when they work as maids for today’s rich descendants of rubber barons. Modern spinoffs include human trafficking, child sex tourism, oil spills, and habitat destruction. Another aspect is that the border zone between Peru and Brazil has the largest concentration of isolated Indigenous peoples. This is no accident. Many are descendants of people who fled into the deep forest to escape the violence.

- - -

b]To read this article, log in here or subscribe here.

If you are logged in but can't read CP+ articles, check the status of your access here

In order to read CP+ articles, your web browser must be set to accept cookies.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/05/28/amazonia-and-the-world/

* * * * *

I can't get this article liberated through the archives site, either, but here is another article which might offer some useful information:

Rubber Barons’ Abuses Live On in Memory and Myth

Indigenous South Americans who lived during the rubber era weave fact and myth to pass down their collective memories as both witnesses and survivors.

By BARBARA FRASER AND LEONARDO TELLO IMAINA

1 JUL 2016

The Kukama people who live along the lower part of Peru’s Marañón River tell intergenerational myths that recollect the violence and trauma of the rubber era, which peaked in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Leonardo Tello Imaina

AFTER HE HAD put them into a deep sleep, the tigre negro entered the camp and killed them all, slashing their throats. It sucked the blood out of them. Only one saved himself by hiding in the forest. From there he heard his companions screaming. That’s how the tigre negro killed the rubber tappers.”

I heard that story from my father when I was a boy, sitting on the palm wood floor of our house on the island of Sarapanga in the Marañón River in northeastern Peru. With smoke from my father’s pipe wafting around us and the river flowing by just meters away, the tale of the tigre negro (literally black tiger, a reference to the black jaguar) capped his late-afternoon storytelling, after which he’d send us off to bed.

Years later, I heard it again as I visited villages with my colleagues from Radio Ucamara, a small station in the port town of Nauta. The members of the radio station staff (including myself, one of the authors, Leonardo Tello) are of the Kukama people, the Native group that predominates in villages along the lower Marañón. The station primarily serves Kukama communities.

When I first listened to it as an adult, the story struck me as odd. The reclusive jaguar is a selective predator, taking only the prey it needs. But gradually, the tale of the animal that slaughtered humans and drank their blood revealed a terrible truth. The tigre negro was not a feline of the forest but something more sinister—a metaphor for a rubber baron. The story captured the living memories of an era when rubber, the once-precious natural latex that drove the Amazonian economy, led to the death or forced displacement of thousands of Indigenous peoples. That reality is as vivid now as it was a century ago when the rubber boom was at its peak.

✽

FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES in the Amazon region, the rubber era was a particularly traumatic part of their collective history.

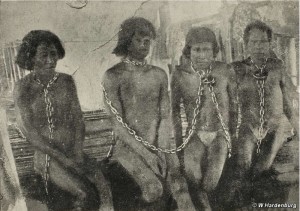

Much of the profit from rubber was gained through the exploitation and abuse of Indigenous peoples in the Amazon. A 1912 book, The Putumayo, in which this image was included, was an early and important work that documented the atrocities committed by rubber baron Julio César Arana’s Peruvian Amazon Company.

More:

https://www.sapiens.org/culture/rubber-era-myths/

~ ~ ~

This article is horrendously sad, painful, and graphic, but it should never have been concealed, like too many others. Those responsible should never have been able to do it in the first place.

Death in the Devil’s Paradise

Little over a hundred years ago, in March 1913, one of the least known, and most shameful, episodes in British colonial history was brought to an end in a London court room. The Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company was wound up in the High Court, the only hint at its dark secrets being a brief remark by the judge that ‘it was impossible to acquit the partners of knowledge of the way in which the rubber had been collected for the company’.

What is known today as the rubber boom had its origin in the middle of the nineteenth century, with Charles Goodyear’s discovery that cooking and treating latex harvested from rubber trees turned it into a product with a huge range of potential uses. With Henry Ford’s mass production of the motor car a few decades later, and the invention of tyres by John Dunlop in 1888, the need for rubber suddenly became extremely pressing.

The rubber tree grew in profusion in the Amazon, especially in its western fringes, and soon a veritable ‘rubber rush’ was on. Entrepreneurs and fortune-seekers set off into the steamy jungle determined to cash in. Unaware of the impending disaster, tens of thousands of Indians for whom the western Amazon was home were experiencing their last years of peace.

One of the many chancers and treasure-seekers determined to make their fortunes in this brave new world was a Peruvian trader named Julio Cesar Arana. Arana acquired vast estates in a region named after its largest river, the Putumayo, and, as many others were doing at the time, realized that only by enslaving huge numbers of the local Indians to collect the latex could his visions of vast wealth become reality. (Slavery had, of course, been abolished decades earlier in the US, but brazenly continued in Amazonia).

Arana and his brother, the aptly-named Lizardo, moved quickly, bringing to Peru from Barbados a large number of overseers well-used to cracking the whip on workers in the British sugar-cane estates. The Bora, Witoto, Andoke and other tribes living in the Putumayo basin were quickly enslaved, and those who escaped the appalling treatment inflicted on them soon fell victim to waves of epidemics brought into remote rivers by traders and rubber-tappers.

More:

https://www.survivalinternational.org/articles/3282-rubber-boom

~ ~ ~

The Putumayo Atrocities

Javier Farje

October 25, 2012

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos apologised on 12 October to the indigenous peoples who suffered as a result of the rubber boom more than a century ago. A delegation of Witotos, Okaina, Bora, Uinona, Miraña, Nonuya and Andokes atended the ceremony in La Chorrera, where the headquarters of the Peruvian Amazon Company was until its dissolution in 1913. Many of these communities were the victims of the rubber boom and it is believed that at least 100,000 died. But, was President Santos right to apologise? After all, most of the atrocities happened when La Chorrera and other camps were part of Peruvian territory. In this extended, two-part article, LAB Editor Javier Farje tells the story of those terrible years that saw hundreds of indigenous communities decimated and sometimes destroyed by the greed inspired by the hunger for rubber.

The Putumayo Atrocities I: what really happened in the Amazon

Walter Hardenburg was a young American engineer who, in 1908, decided to throw in his lot with a band of adventurers travelling to the depth of the Amazon rainforest to join the rubber boom. He planned to work on the construction of a railway that would link the Brazilian town of Madeira with Mamoré, in Bolivia. He never reached his destination. Instead, he fell into the hands of the Peruvian Amazon Company, PAC, the biggest rubber venture on the Peruvian side of the border with Colombia.

During his time in the cells of the PAC’s guards, he witnessed sights he didn’t think possible in the 20th Century: hundreds of Indians flogged, carrying heavy balls of untreated rubber or supplies into warehouses controlled by “muchachos”, young Barbadian gang-masters who had been recruited by the owner of the PAC, Julio César Arana.

This was the harsh reality of the rubber boom in the South American Amazon, fuelled by the insatiable hunger of the industrial world for the crucial raw material that kept cars and machines going.

The discovery of the trees Hevea Benthamiana, the Hevea Brasiliensis and the Hevea guyanensis by the banks of the rivers Putumayo and Igaraparaná in the late 19th Century brought a wave of explorers and adventurers to the merciless forests of what is now Peru, Brazil and Colombia. These types of rubber were considered the best for industrial consumption. The rubber trees grew in indigenous territory, where Witotos, Boras and Andoques, among other groups, lived with little contact with the whites.

At the start of the rubber boom, mestizos and Christianised Indians were the main sources of labour for the incipient rubber barons, mainly Colombians, Brazilians, Bolivians and a few Peruvians. Rubber entrepreneurs preferred the Indians because they were less greedy than the mestizos. Hildebrando Fuentes, a Peruvian liberal politician who held various officials posts in Loreto, described the Indians as “loyal…they accompany the rubber tapper for a long time. The mestizos are intelligent but they only help their bosses enough to earn money they will later use to have fun and become independent.”

More:

https://lab.org.uk/the-putumayo-atrocities/